NOTE: The history of the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II is broader than one blog post can explain fully. We encourage readers to explore other resources on the topic, including primary sources from the National Archives and Records Administration and the resources listed at the end of the page.

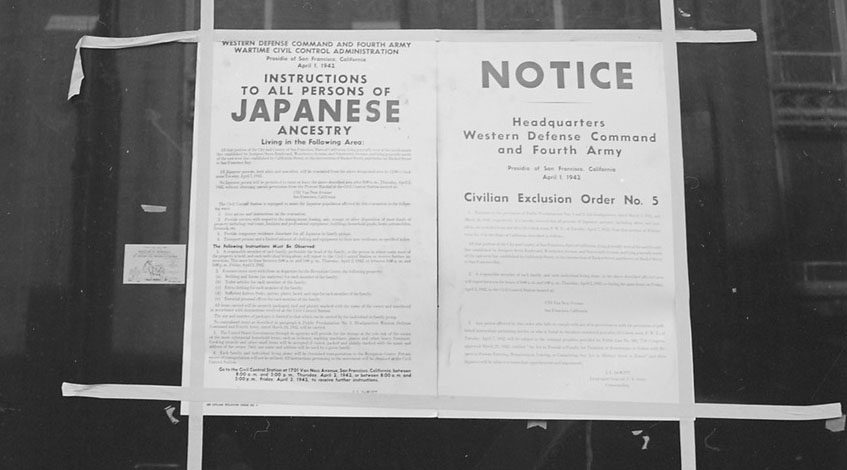

During World War II, upon the order of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the United States government placed approximately 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry into incarceration in concentration camps. Executive Order 9066, signed on February 19, 1942, gave the army authority to “evacuate”[1] Japanese Americans from the West Coast.[2] Roosevelt created the War Relocation Authority (WRA), the U.S. civilian agency responsible for the relocation and detention of Japanese Americans. Under operations overseen by the WRA, Japanese Americans[3] were evicted from their homes and incarcerated in one of ten remote concentration camps, euphemistically termed “relocation centers.”[4] The eviction process lasted from March to August of 1942. As part of the forced relocation, each family was limited to bringing only as much as they could carry of their clothing, bedding, eating utensils, toiletries, and “essential personal effects.”[5]

Under the authority of the executive order, the Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA) was established as part of the Western Defense Command to handle the logistics of the forced removal.[6] The WCCA managed the activities of the civilian agencies involved in the effort, which included the Federal Security Agency; the U.S. Employment Service; and the Farm Security Administration, in charge of handling the transfer of farm properties. Temporary camps, termed “assembly centers,” were established by the WCCA to gather and register large groups of Japanese Americans before their transfer to distant camps. The WCCA’s last act before its dissolution and the closure of the assembly centers was to load detainees onto trains bound for the long-term incarceration centers (concentration camps) managed by the WRA.[7]

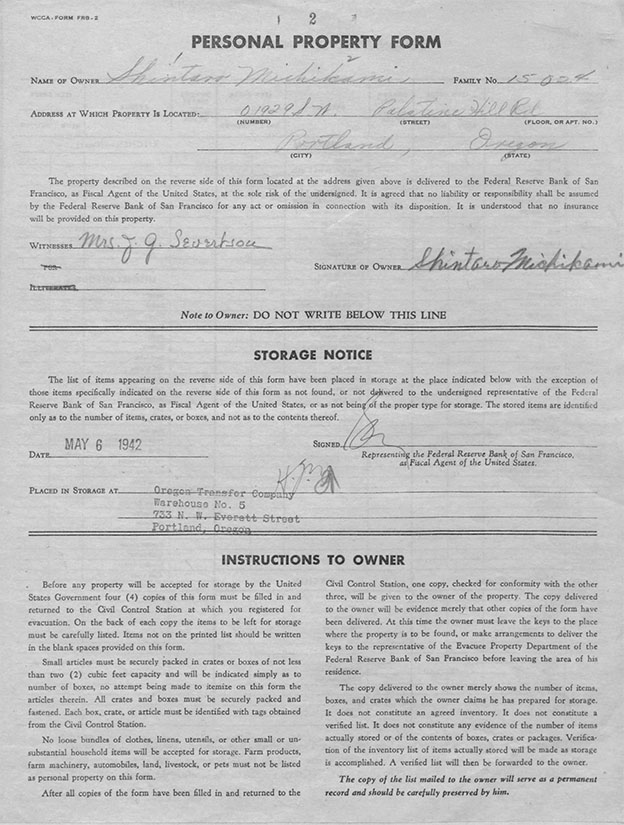

In March 1942, Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau Jr. asked the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco to act as a fiscal agent and undertake certain activities to help Japanese Americans protect their property.[8] General John L. DeWitt, lieutenant general of the U. S. Army, directed the Federal Reserve to “carry out the objective of the program,” as part of the WCCA, and provide property disposition services to those requesting them. The Federal Reserve was given two tasks: first, to help Japanese Americans that were forced to abandon their possessions avoid being defrauded by potential buyers; and second, to aid the war effort by transferring property as quickly as possible so that the large number of sales would cause “minimal disruption of the local economy.”[9] In response, the Federal Reserve moved quickly, setting up an Evacuee Property Department in just two weeks. Branch offices were established in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Portland, and Seattle; 49 field offices were opened throughout the Twelfth District; and at the peak of operations, 184 employees were directly engaged in the duties of the department.

Though the 27,000 cases handled by the Federal Reserve reflected only a small portion of the total number of individuals and families forced to relocate, the system was quickly overwhelmed by the enormouisness of the task and the tight deadline.[10] Most of those forced to relocate had less than two months between notice of evacuation and removal, leaving them little time to manage their properties and belongings.[11] Assistance provided by the department varied, depending on the nature of the request. In some cases, a phone call or a letter sufficed. In others, agents met and interviewed those asking for help. The tasks the agents helped with included the selling and storing of household goods and vehicles and the selling of small businesses and property. Agents also provided referrals to other agencies.

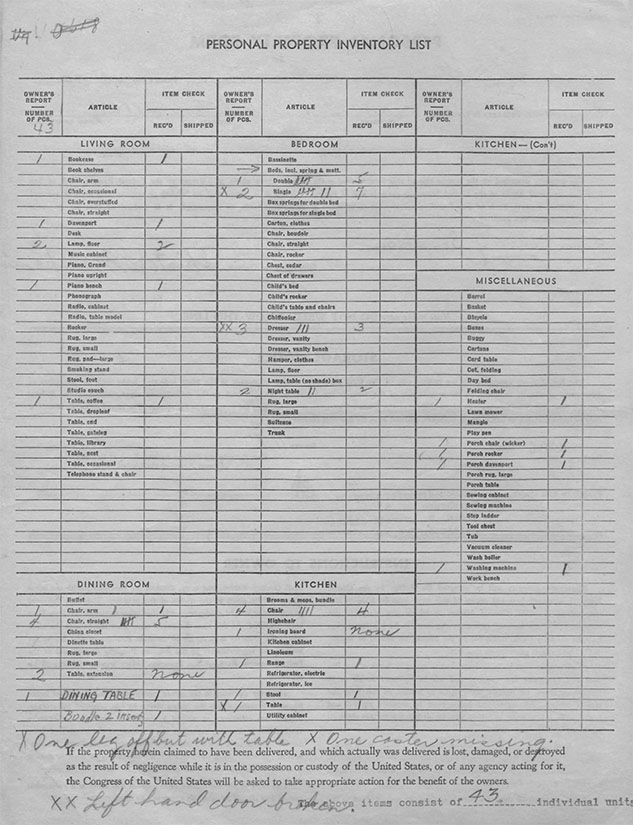

Personal property inventory list of the family of Shintaro Michikami, Family No. 15024, May 6, 1942. Records of the War Relocation Authority, Record Group 210.

The records from the San Francisco and Portland branches of the department, included in Record Group 210: The Records of the War Relocation Authority, document the Federal Reserve’s work assisting with the disposition of property. A significant portion of these records is correspondence and interviews with Japanese Americans from the West Coast. The records also include a variety of other documents, including property inventories, receipts, and lists of “contraband” taken from individuals at the temporary camps (including everyday items such as cameras, radios, and flashlights).

Historian Sandra Taylor concluded that, with minimal time to prepare and a largely peacetime expertise, the primary goal of the Federal Reserve was timely performance of its duties, which took precedence over equity for the Japanese Americans.[12] In 1988, the Civil Liberties Act granted reparations to those who had been interned by the U.S. government during World War II. The legislation acknowledged that the government’s actions had been based on “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.”[13] While the economic toll on the people who were imprisoned by the U.S. government during World War II may not ever be fully known,[14] these records provide an opportunity to begin to understand the enormity of their losses.

The Bank’s Evacuee Property Department ended operation on December 31, 1942. With its assignment completed, the San Francisco office turned over some of its records to the WRA, who made indexes of the contents of the paperwork and destroyed the originals. Some of the records remained with the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco and were transferred to microfilm. In 2007, a portion of the records related to the activities of the Portland branch of the department were discovered, and in 2014 these records were digitized by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. In 2016, the digitized microfilm records of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, as well as physical records (and digitized files) of the collection created and held by the Bank’s Portland Branch, were transferred to the National Archives, which made them available online. In partnership with our colleagues at the San Francisco Fed and the National Archives, these records are available on FRASER to increase access to the materials, provide connections to related materials from Federal Reserve archival collections, and maximize opportunities for scholarly research and education.

Selected Educational Resources

Densho: The Japanese American Legacy Project. Densho Encyclopedia.

Japanese American Citizens League. The Power of Words Handbook. April 27, 2013, revised August 2020.

Nolan Cool. “Leaving Home Behind: The Fates of Japanese American Houses During Incarceration.” O Say Can You See? (blog), National Museum of American History, August 3, 2017.

National Archives and Records Administration. “Japanese-American Internment During World War II.” N.d.

National Archives and Records Administration. “Japanese Relocation and Internment” (list of resources). N.d.

National WWII Museum. “Japanese American Incarceration Education Resources.” February 19, 2021.

War Relocation Authority. “The Evacuated People: A Quantitative Description” (a 1946 census of those of Japanese ancestry incarcerated in camps during WW II). U.S. Department of the Interior, 1946.

[1] See the Densho Japanese American Legacy Project for an explanation of the terms used to describe these historical events.

[2] Of those of Japanese ancestry interned, nearly two-thirds were American citizens born in the United States. Those who were not citizens included longtime U.S. residents barred from naturalization by extreme restriction on immigration from Asia. As used here, the term “Japanese Americans” is meant to be inclusive of all of those of Japanese ancestry interned.

[3] Although people of Italian and German ancestry were also targeted by the order, they were mostly placed under restrictions such as a curfew: David A. Taylor. “During World War II, the U.S. Saw Italian-Americans as a Threat to Homeland Security.” Smithsonian Magazine, February 2, 2017.

[4] See images of barracks, common areas, and documentation of daily life in internment camps in the University of California’s Voices in Confinement: A Digital Archive of Japanese-American Internees.

[5] J.L. DeWitt. “Civilian Exclusion Order No. 5.” Western Defense Command and Fourth Army, April 1, 1942.

[6] Brian Niiya. “Wartime Civil Control Administration.” Densho Encyclopedia, October 8, 2020.

[7] Niiya.

[8] The Treasury Department enacted restrictions on Japanese Americans throughout 1941 (as well as on Italian and German Americans) following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, despite the fact that no Japanese national residing in the United States or Japanese American had been found guilty of sabotage or espionage.

[9] Sandra C. Taylor. “The Federal Reserve Bank and the Relocation of the Japanese in 1942.” Public Historian, 5(1), 1983.

[10] To understand the economic challenges and hardships associated with a rapid and forced relocation, see the Federal Reserve History essay “The Federal Reserve’s Interactions with Japanese Americans During WWII.”

[11] Taylor, p. 10.

[12] Taylor, p. 30.

[13] 100th Congress, S. 1009, 1987 (reproduced at internmentarchives.com).

[14] Natasha Varner. “Sold, Damaged, Stolen, Gone: Japanese American Property Loss During WWII.” Densho Blog, April 4, 2017.

© 2023, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.

@FedFRASER

@FedFRASER