FRASER launched to the public nearly 15 years ago, on July 1, 2004, as a supplement to FRED®, allowing researchers to access sources (largely original data releases) previously available only in printed form.[1] At the time of its launch, FRASER had around 500 PDFs. Since then, we have grown this digital library to over half a million items documenting U.S. economic, financial, and banking history—particularly the history of the Federal Reserve System.

So, how well do you know FRASER? Our librarians show off some of FRASER’s hidden gems in our treasure hunt…

1. What was the first title added to FRASER?

If you look closely at URL structure in FRASER, you’ll figure out that we started with Economic Indicators, title ID #1. If you try to figure out what title ID #2 is by going straight to that URL, you’ll be out of luck; our second title is actually Annual Statistical Digest, title ID #7—as content has been reorganized and renumbered over the years, publication (and author) numbers have been deleted or retired.

2. What is the oldest item on FRASER?

Since we know the first item on FRASER is part of Economic Indicators, let’s find out about the oldest item according to original creation date by the item’s author.

The oldest historical document on FRASER is Plan for Establishing a National Bank in the United States of North America, a document from the Continental Congress of May 17, 1781. You can Browse by Date to identify this item’s place in our collection’s chronology.

Keen-eyed FRASER users will see a note on the bottom of that page that the document’s digital origin is “LC American Memory.” The digital copy was extracted from Journals of the Continental Congress, available from the Library of Congress. The oldest item scanned by the FRASER team is An Inquiry Into the Nature and Effects of the Paper Credit of Great Britain, written by Henry Thornton in 1807.

3. What is the newest item on FRASER?

This answer is constantly changing. As described above, you can Browse by Date to find content created this year so that will get you close to the most current answer. We monitor several publications and add new issues to FRASER as they are published, so our “newest” item at any given point in time is generally less than a week old.

You can keep up with the latest additions to FRASER by subscribing to our What’s New RSS feed with your favorite RSS reader. The latest five additions are always listed on the FRASER homepage in the “What’s New” section, and they also appear at the top of the What’s New page that lists new additions going back to 2006!

4. What is the biggest collection on FRASER?

The Call Reports collection contains balance sheet and income statement information for thousands of commercial banks dating 1916-1959. The collection was digitized from 739 reels of microfilm containing over 1,000,000 images, represented as over 400,000 items on FRASER. More explanation of this collection is available in another Inside FRASER article.

5. What is our biggest item?

The answer to this question depends on how you define “big.”

The 1904 Annual Report of the Comptroller of the Currency (Volume 2) contains 1,847 pages and is our largest single PDF document by page count. That being said, we do sometimes split PDFs to keep file sizes small (or at least not quite as enormous). An example of this is the January 1910 issue of Rand McNally Bankers’ Directory—a single bound volume of 1,680 pages (just over one-half gigabyte in size) was split into 16 PDFs for a more user-friendly presentation on FRASER.

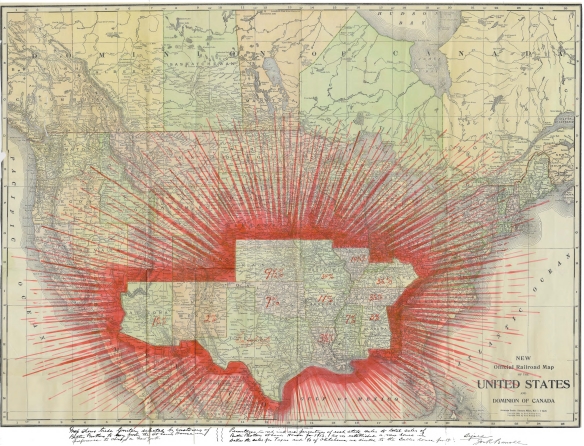

For an alternate measure of “big” there’s 75 Yrs. of American Finance: A Graphic Presentation, 1861 to 1935, which was published as a continuous timeline over 85 feet long. The Map of the United States Showing Sales Reach of the Butler Brothers Company of St. Louis, circa 1913, is a little bigger than 3 x 4 feet. It’s part of the records of the Reserve Bank Organizing Committee (the committee that chose the 12 Federal Reserve Bank locations).

6. What is our smallest item?

This is a tough one. We have thousands of single-page documents in addition to small pamphlets.

The Committee on the History of the Federal Reserve System collection contains a “catalog” of 3×5 index cards. Some of our archival collections contain business cards, which may be the smallest pieces of paper scanned for FRASER. The FDIC’s pocket-sized Instructions to Examiners may be our smallest book, at just 3.5 x 5.5 inches.

7. What is the most unusual item on FRASER?

Different users probably have different opinions on this. Possibilities include a song written by Charles S. Hamlin, who would later become the first Governor of the Federal Reserve Board; or Wonderland Revisited, an unsigned four-page parody of the Mad Hatter’s tea party from Lewis Carroll’s novel Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, discussed in another Inside FRASER article. While these items are certainly unusual within the context of FRASER, sheet music and parodies of popular literature are not so rare in broader contexts.

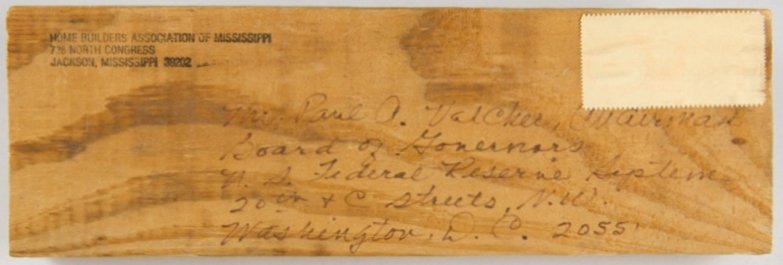

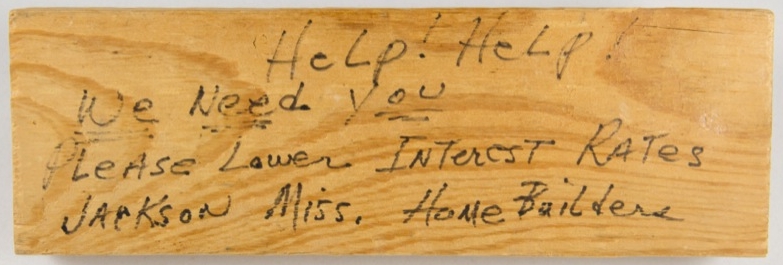

A wood 2×4 was sent to Fed Chairman Paul Volcker by the Jackson, Mississippi, Home Builders, who were concerned about interest rates. Their message was written on the back of the 2×4, as if it were a postcard. As an artifact, rather than a document, this is definitely one of our more unusual items.

8. What is the longest-running publication on FRASER?

FRASER has over 200 years of content available on the Annual Report of the Secretary of the Treasury on the State of the Finances, covering 1789-1980, making it our longest-running publication. The Annual Report ceased publication after 1980, but data found in the annual report is available for recent years in the Treasury’s Agency Financial Report, the Treasury Bulletin, the Combined Statement of Receipts, Outlays, and Balances of the United States Government, and in annual reports of other bureaus of the Treasury.

9. What is the most common file type on FRASER?

If you have spent much time at all on FRASER, you probably know the answer to this: PDF. When FRASER was started, the only file type our system supported was PDF. Over the years, as we have grown our collections, we have added support for additional file types, including image, audio, and video formats—which leads into the next question:

10. What is the newest file type on FRASER?

Recently, we added Excel and CSV formats to our supported file types, letting us present materials in the spreadsheet format so frequently requested by users. See our first example in the Treasury TARP reports.

11. When did we start tweeting?

@FedFRASER’s first tweet went out on June 5, 2013:

Like most Twitter users, we aren’t perfect! Although we work hard to make sure our tweets are historically interesting and factual, we do make mistakes—like misspelling poor Wilber’s first name.

12. Who was our first official partner?

Our very first FRASER partnership was with the GPO (then called the Government Printing Office, now the Government Publishing Office) in 2005 to provide permanent public access to digitized Federal Depository Library Program (FDLP) publications. Details of this and other partnerships are available in the Inside FRASER article Librarian Life: Digitization Partnerships.

13. What was the first archival collection digitized for FRASER?

We began digitization of the William McChesney Martin, Jr. Papers all the way back in 2006. This collection, held at the Missouri History Museum in St. Louis, was brought to light when we were digitizing the primary source documents used by Alan Meltzer for his volumes of A History of the Federal Reserve. When we realized that the papers by Martin, the longest-serving chairman of the Board of Governors, were practically right in our backyard, we formed a partnership with the Missouri History Museum to digitize the papers and make them available on FRASER. More details on this collection are available in the Inside FRASER article Librarian Life: Organization of Digitized Archival Collections.

14. What was our first born-digital collection?

The majority of content on FRASER has been digitized: An analog object is captured (scanned, recorded, photographed) and translated into a digitally encoded format. Some materials are born digital, meaning they began their life as a digital product.

We have been adding both digitized and born-digital content to FRASER since the beginning. When FRASER went live in 2004, it had the latest born-digital issues of Economic Indicators, in addition to older issues that had been scanned.

Our first experience working with born-digital materials on a large scale was with the Financial Crisis materials. During the Financial Crisis of 2007-2009, the St. Louis Fed created a timeline to capture the events and the policy responses with links to original source documents. As time went on, these original source documents began to disappear or move to new locations. FRASER staff undertook a project to capture all the documents linked from the timeline, as well as other documents from the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission and from government agencies involved in the response to the financial crisis.

The materials went live on FRASER in 2016. The project is discussed in greater detail in a recent Inside FRASER article: Librarian Life: Preserving the Financial Crisis Timeline.

15. Finally, just how much stuff is in FRASER?

In total, FRASER has over 575,000 PDFs amounting to over 5

million pages. At 2,000 pages per linear foot, 5 million pages would span nearly

a half mile in length. It would take 19 years of continuous reading at an

average rate of 2 minutes per page to read all 5 million pages—not counting

time for sleeping or eating—and just imagine how far behind you will be with

all the new content we will have added in that time! On top of that, there are

nearly 500 video and audio files amounting to over 3 weeks of content (again,

no breaks for sleep).

[1] Robert Rasche, Katrina Stierholz, Robert Suriano and Julie Knoll. “As It Happened: Economic Data and Publications as Snapshots in Time,” Presented at the Fall Federal Depository Library Conference. October 19, 2004.

© 2019, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.