Inside FRASER recently provided an in-depth look at many women who were the first in their careers—from the first woman director of the United States Mint, to the trailblazing women behind the Women’s Bureau, to the first woman to serve on the Federal Reserve Board. This month, FRASER continues to celebrate the contributions of women in the economy with a profile of Frances Perkins, “the woman behind the New Deal.”

On March 4, 1933, Frances Perkins took office as the Secretary of Labor, nominated by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Perkins would have been famous for being the first woman member of a presidential cabinet, but it would be her continued accomplishments—the creation of Social Security, unemployment insurance, a federal minimum wage, and federal laws regulating child labor—that would construct and solidify her legacy in American history.

Taking an unconventional path for a woman in her time, Frances graduated from Mount Holyoke college in 1902 and later obtained a graduate degree in political science at Columbia University.[1] Early in her professional career, Perkins worked for the New York City Consumers League as their executive secretary where she lobbied for workers’ rights regarding health and safety, the limitation of work hours, and the elimination of child labor.[2] During this time, Perkins witnessed the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire on March 25, 1911, which claimed the lives of 146 workers, most of them young women. After the tragedy, Perkins, along with other concerned citizens, set out to form a legislative commission “to devise ways and means to prevent accidents by fire in the State of New York.”[3] Perkins served as the investigator of the Factory Investigating Commission, and in a lecture given to students at Cornell University, she said they “kept expanding the function of the commission ‘till it came to…report all kinds of human conditions that were unfavorable to the employees.”[4] Over the course of the commission, Perkins became acutely aware of the hardships faced by many workers and strengthened her resolve to advocate for their rights.

In 1918, Frances Perkins achieved one of the many “firsts” in her career when New York’s governor, Al Smith, chose her to serve on the New York State Industrial Commission, becoming the first woman to hold an administrative position in the state’s government. When Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected governor of New York in 1929, he appointed Frances Perkins New York State Industrial Commissioner. During her tenure, she became known for her establishment and enforcement of safety standards, her work toward better hours and conditions for women in industry, and the passage of bills intended to revolutionize labor and industry in New York State.[5] Perkins’s interest in establishing programs to increase employment and an unemployment insurance program came into focus when the stock market crashed in autumn 1929. The crash signaled the beginning of the Great Depression, a national trial against which Perkins would prove to be a formidable opponent in the years to come.

When Roosevelt and Perkins were sworn into office in March 1933, neither wasted any time in waging battle against the nation’s economic downturn. They began to form a series of programs, financial reforms, public work projects, and regulations that would become known as the New Deal. In April 1933, the Roosevelt administration established the Emergency Conservation Corps (later known as the Civilian Conservation Corps, or CCC) to both provide jobs for unemployed young men and conserve the nation’s natural resources.[6] Through the Wagner-Peyser Act, signed into law in June 1933, Perkins oversaw the establishment of a nationwide system of public employment offices (later known as the Employment Service),[7] followed by the passage of the National Industrial Recovery Act, which allowed the Roosevelt administration to regulate industry for fair wages and prices to stimulate economic recovery. In February 1934, Perkins presided over the National Conference for Labor Legislation, which discussed key objectives for future labor reform, such as minimum wage, regulations for child labor, a shorter work week, unemployment insurance, and old-age pensions.

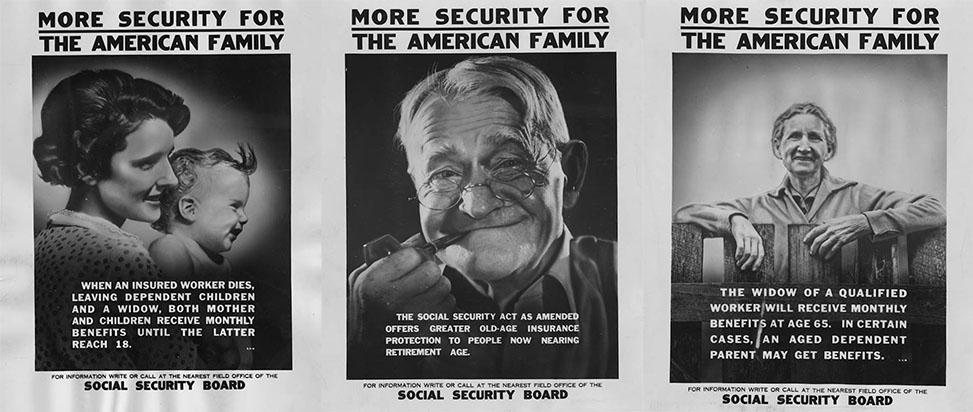

In June 1934, Roosevelt issued an executive order to establish the President’s Committee on Economic Security, with Perkins at the helm. Its objective was “to study the problems relating to economic security and to make recommendations, both for a long-time and an immediate program of legislation which would promote economic security for the individual.”[8] The committee’s final report laid the foundation for the Social Security Act and outlined the recommended legislation. After sending the report to Congress, President Roosevelt signed the act in 1935. Shortly after its passage, Perkins expertly explained and defended the act on the NBC Radio Network program America’s Town Meeting of the Air.

With Perkins’s support, Congress passed the National Labor Relations Act in 1935 to protect the rights of employees to bargain collectively, prevent unfair labor practices, and establish the National Labor Relations Board. Continuing with her New Deal initiatives, Perkins helped draft the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. The act created a minimum wage, established overtime pay when working over 40 hours a week, and prohibited “oppressive child labor.”

After 12 years of service in the Office of the Secretary, Perkins became the longest-serving Secretary of Labor and one of two cabinet officials to serve through the entirety of Roosevelt’s presidency. A year after she resigned from her cabinet position, President Truman asked Perkins to be a member of the United States Civil Service Commission, which she served on until retiring from government service in 1952. Perkins continued to teach and lecture at Cornell University’s New York State School of Industrial and Labor Relations until her death in 1965.[9] In recognition of Perkin’s accomplishments, the Department of Labor Headquarters was renamed in her honor in 1980.[10]

[1] Breitman, Jessica. “Honoring the Achievements of FDR’s Secretary of Labor.” FDR Library Blog.

[2] Breitman. See footnote 1.

[3] Lecture by Frances Perkins given September 30, 1964. Collection /3047, Cornell University, Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, Ithaca, NY.

[4] Lecture by Frances Perkins. See footnote 3.

[5] Parkhurst, Genevieve. “Frances Perkins, Crusader.” Evening Star [Washington, D.C.], February 19, 1933.

[6] Salmond, John. The Civilian Conservation Corps 1933-1942: A New Deal Case Study. North Carolina: Duke University Press, 1967.

[7] “Wagner-Peyser Act of 1933, as amended.” Department of Labor, Employment Training Administration.

[8] Committee on Economic Security. Social Security in America: The Factual Background of the Social Security Act as Summarized from Staff Reports to the Committee on Economic Security. Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1937.

[9] “Her Life: The Woman Behind the New Deal.” Frances Perkins Center.

[10] “Hall of Secretaries: Frances Perkins.” U.S. Department of Labor.

© 2021, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.

@FedFRASER

@FedFRASER