In 1907, a financial crisis shook the world economy. The Panic of 1907 was marked by a series of bank runs, prompted by Otto Heinze’s failure to corner the market on the United Copper Company’s stock and the Knickerbocker Trust Company’s subsequent collapse. The banker and financier J. P. Morgan prevented the crisis from worsening by raising funds to help prop up struggling financial institutions.[1]

In the aftermath of the Panic of 1907, Progressives—reformers dedicated to achieving social progress and, in particular, reducing economic inequality—called for greater government regulation of the nation’s financial system. Anti-bank Congressman Charles A. Lindbergh, Sr., introduced a resolution to investigate financial institutions.[2] These efforts led to the creation in 1912 of the Pujo Committee, a congressional subcommittee named after its chairman, Congressman Arsène Pujo, a former member of the National Monetary Commission. The committee investigated what they called a “money trust,” a group of Wall Street bankers and financiers accused of consolidating control over the nation’s financial institutions. According to the committee, the money trust threatened to undermine competition by concentrating economic power in the hands of a few men.

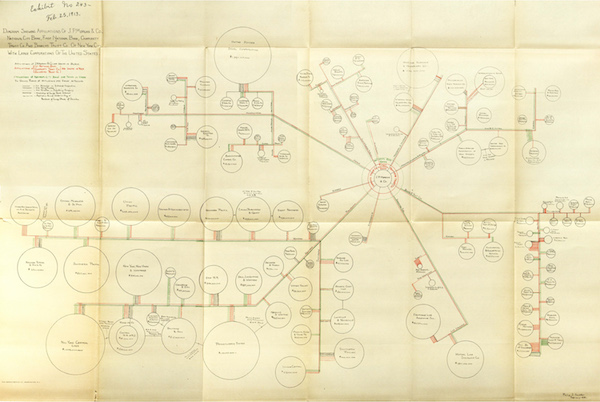

The Pujo Committee held hearings from May 16, 1912, to February 26, 1913, and released its final report in 1913. It identified six banking houses responsible for increasing the concentration of money and credit: J. P. Morgan & Co.; First National Bank of New York; National City Bank of New York; Lee, Higginson & Co., of Boston and New York; Kidder, Peabody & Co., of Boston and New York; and Kuhn, Loeb & Co. The committee drew attention to the interlocking directorates that connected the major banking houses to one another, in which individuals served on the boards of directors of multiple banks. It found that the banks of Morgan, National City, First National, Guaranty Trust Co., and Bankers’ Trust Co. held 341 directorships in 112 corporations and controlled over $22 billion in resources (1913 dollars).[3] In its final report, the committee recommended that new regulations be placed on banks, clearing house associations, and the New York Stock Exchange.

Diagram illustrating interlocking directorates connecting the banks of Morgan, National City, First National, Guaranty Trust Co., and Bankers’ Trust Co. https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/80/item/23678.

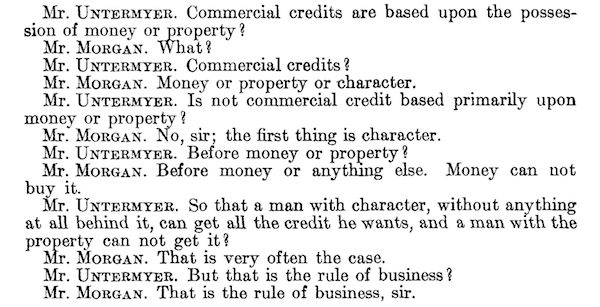

The committee labeled J. P. Morgan & Co. the recognized leaders of the “inner group” of the money trust. Called to testify before the committee, Morgan was questioned by Samuel Untermyer, the committee’s counsel. Morgan emphasized the role of character in banking and spoke of the moral responsibility assumed by banking houses during the course of their business.

J.P. Morgan’s testimony before the Pujo Committee. https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/80/item/23671?start_page=76.

The Pujo Committee’s inquiries drew criticism from some business advocates. For example, the weekly newspaper Commercial and Financial Chronicle claimed that the hearings were “more in the nature of a prejudiced cross-examination than of a fair and unbiased inquiry into the facts.” By contrast, the progressive lawyer Louis Brandeis praised the Pujo Committee’s efforts to expose the inner workings of “our financial oligarchy” in Other People’s Money: And How the Bankers Use It, published in 1914.

In its final report, the committee concluded that “there is an established and well-defined community of interest between a few leaders of finance…which has resulted in great and rapidly growing concentration of the control of money and credit in the hands of these few men.” This declaration shaped the development of economic policy during Woodrow Wilson’s presidency. Wilson’s New Freedom agenda centered on limiting economic concentration to protect competition.[4]The Pujo Committee’s findings influenced the passage of major legislation during the Wilson administration, including the Federal Reserve Act of 1913, which established a decentralized national banking system[5]; the Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914, which created a federal agency empowered to investigate antitrust violations[6]; and the Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914, which regulated interlocking directorates.[7]

The Pujo Committee’s full hearings and report are available on FRASER. For more information on the Pujo Committee and the Panic of 1907, check out this classroom lesson and our FRASER Quick Look.

[1]Ron Chernow. The House of Morgan. Grove Press, 2010: 122-128.

[2]Charles Geisst. Wall Street: A History. Oxford University Press, 2012: 123.

[3]Ibid., 125.

[4]Julia C. Ott, When Wall Street Met Main Street. Harvard University Press, 2011: 31.

[5]Chernow, House of Morgan, 156.

[6]Ott, When Wall Street Met Main Street, 33.

[7]Vincent P. Carosso, “The Wall Street Money Trust from Pujo through Medina,” Business History Review 47, no. 4 (1973): 428.

© 2019, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.