July 1, 2019, marked the 15th anniversary of the launch of FRASER®! It is part of a longstanding tradition[1] at the St. Louis Fed of disseminating data to the public, dating back to the 1960s when the Bank earned its reputation as a “maverick” in both its economic thought and its commitment to sharing information with the public. FRASER was originally created as an adjunct to the well-established FRED® data aggregator (launched in April 1991). The collection started with a handful of scanned statistical publications, one data release from the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, and one Senate document related to the Federal Reserve Act. Though humble in comparison to today’s collection of more than half a million documents, the digital library landscape of 2004 was a vastly different world. The first version of FRASER—then going by the cumbersome name “Federal Reserve Archival System for Economic Research”—predates two of the largest and best-known digitized collections still in operation: Google Books and the Internet Archive’s Open Library, both of which launched in late 2005.[2]

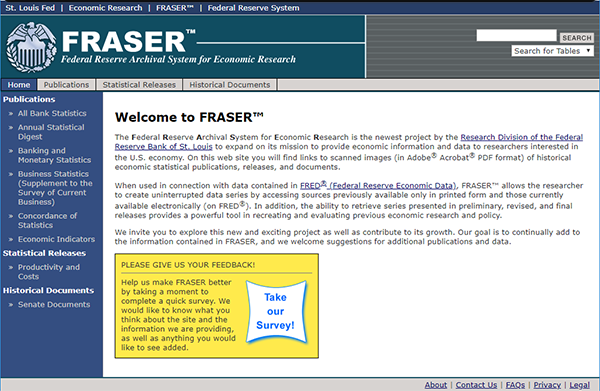

Unlike those library projects, FRASER was intended first and foremost to serve the needs of economic policy analysts. In one of its earliest designs, the site declared that “the ability to retrieve [economic data] series presented in preliminary, revised, and final releases provides a powerful tool in recreating and evaluating previous economic research and policy.”

FRASER’s look in September 2004 (image via the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine)

Then St. Louis Fed Research Director Robert Rasche, who was instrumental in the creation of FRASER, said in a presentation at the Federal Depository Libraries Conference in 2004 that to understand the “expectational forces” that sway the economy, economists need to be able to see the data as they were published. Data on FRASER, which are frozen in a specific moment, show the information that policymakers at the time would have used to make their decisions. Those policymakers used their best judgment to forecast the near economic future but lacked the benefit of later corrections and revisions of the data. Having the contemporaneous account helps researchers understand those historical decisions. Though economic data are still one key focus, FRASER’s philosophy has since evolved.

With the help of its small digitization team, FRASER grew slowly but significantly in the first few years, expanding the collection to encompass Federal Reserve history, not just data. Between 2006 and 2009, FRASER digitized research materials Allan H. Meltzer used for his first volume of A History of the Federal Reserve; a collection of personal papers of William McChesney Martin Jr., the longest-serving Fed chairman;[3] and papers from the Brookings Institution’s 1950s research project known as the Committee on the History of the Federal Reserve System. These projects expanded our fledgling partnership program to include not just government and Fed documents and archives, but materials held by individuals, research institutions, and museums. For FRASER’s fourth birthday in 2008, the digitization team established its own broader mission to “preserve the nation’s economic history”[4] through its work on FRASER and other projects. This refocused team contributed to a new and improved FRASER that boasted “photographs, manuscripts, and multimedia formats” in addition to scanned text publications and aimed to appeal to a broader audience interested in economic and policy history.

Between its fifth and tenth birthdays, two major historical events—an anniversary and a world-wide economic crisis—transformed FRASER into its modern form. Because the Financial Crisis of 2007-2009 (and concurrent Great Recession) had many parallels to the Great Depression, the public had an appetite for economic history materials that could show how a financial crisis unfolds. FRASER responded by digitizing the reports of the Money Trust Investigation (1912-1913), the Pecora Commission (1932-1934), and many reports and data publications on mortgage crises, bank failures, and bailouts. The team also worked to capture the events of the ongoing crisis as they occurred, identifying materials for the Financial Crisis Timeline in partnership with other St. Louis Fed colleagues. Just as the Great Recession was coming to an end, preparations for the commemoration of the Federal Reserve’s upcoming centennial in 2013-2014 were beginning. The FRASER team used this opportunity to digitize dozens of boxes of materials from the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), including the records of the Reserve Bank Organization Committee (which determined the location and boundaries of the Federal Reserve Districts) and the two precursors to the Federal Open Market Committee.

FRASER spent much of its first decade finding its identity in a quickly evolving information landscape. Although the name stayed the same, FRASER’s logo and its tagline changed over time as we considered how best to tell our users about our work and its benefits. Although we had often informally described FRASER as a digital archive or data preservation project, that changed as library terminology shifted and digital archiving and digital preservation became better-established practices. In 2009 the site’s stated goal was “to contribute to the quality of scientific economic research through the creation of a public electronic archive of economic statistical publications and data.” As the work changed, the wording of the mission shifted to include the goal to “preserve and provide access” and later to “safeguard and provide easy access” to economic history. In recent years, talking about FRASER as a digital archive or a site that preserved data made less sense as those phrases took on specific technical meaning.

In the lead-up to the 2013 Federal Reserve centennial, with the launch of major new collections, the team’s renewed focus became connecting people to our collections. FRASER librarians worked diligently to broaden access, joining partners across the state to found the Missouri Hub for the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA) and sharing our collections with the public through a FRASER Twitter account. Finally, FRASER was finding its stride as a robust digital library, with the launch of the new, more user-friendly site design in 2014 and increased staff emphasis on cataloging and metadata, collection development, and partnerships with teachers and researchers. As an April 2015 College and Research Libraries News review of FRASER reported, the site’s new goal was “to safeguard and provide easy access to economic history.”

Today, through our continual additions of content, this blog, staff presentations at library and education conferences, social media, and other outreach, the FRASER team works to share that invitation with the widest possible audience. We are grateful to our colleagues, partners, and community of users for helping us grow, and we’d love to hear your ideas about what our next 15 years of discovering economic history should look like.

[1] This dissemination began in 1961 with three tables of data and this letter from Research Director Homer Jones. According to this 2006 speech from William Poole, then St. Louis Fed President, the three tables were M1; money supply plus time deposits; and money supply plus time deposits plus short-term government securities.

[2] National Public Radio. “Google Announces Plans to Digitize Public Library Holdings.” Morning Edition, December 14, 2004. Michael Bazeley. “Alliance Aims to Digitize Classic Books.” The Seattle Times, October 24, 2005.

[3] A Missouri native, Martin’s personal papers are held by the Missouri History Museum

[4] Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. “St. Louis Fed Introduces Digitized Archives.” Press release, July 3, 2008.

© 2019, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.