A common adage among FRASER staff is “the perfect is the enemy of the good.”[1] In archival circles, this idea is often described as “more product, less process” (MPLP).[2] The gist of it is this: While we strive to produce excellent images, detailed and informative descriptions, and superior tools for discovery and navigation, we could spend so much time perfecting these details that we would produce only miniscule amounts of content. In a 2015 survey of FRASER users, we received an overwhelming response for more content over other improvements. So, in addition to implementing various automation methods to improve efficiency, we have developed digitization and metadata standards that help us produce greater amounts of good (but not perfect) content. One application of this concept to FRASER projects can be seen through the changes in our processes for digitizing archival collections.

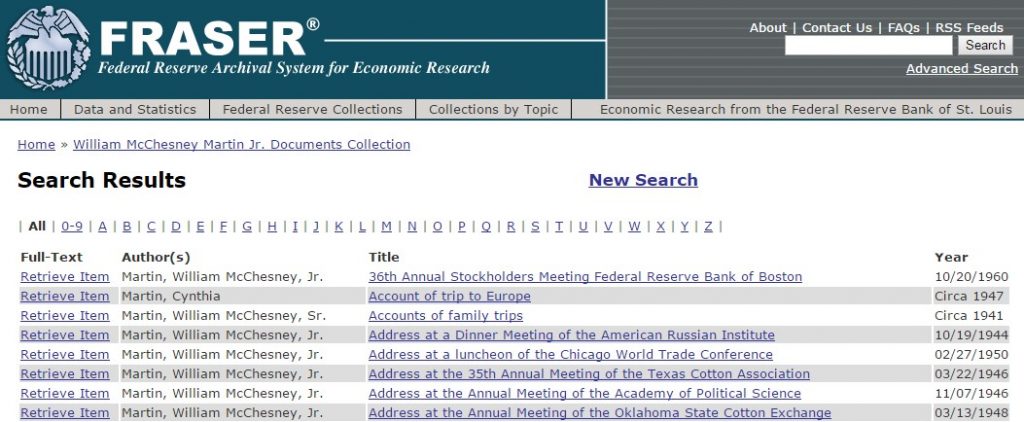

Our first experience in digitizing an archival collection was with the William McChesney Martin, Jr., Papers held at the Missouri History Museum Archives. Beginning in 2006, FRASER staff reviewed the collection, item by item, and selected individual items for digitization, particularly those relating to Martin’s involvement with the Federal Reserve System, Export-Import Bank of Washington, and Treasury.[3] These selected items, amounting to approximately 11,000 pages, were digitized and made available on FRASER. These individual items were given detailed descriptions written by FRASER staff after reading and evaluating each item. To supplement the collection, additional materials relating to Martin and his career were added to FRASER, such as Newsreel Footage of Martin’s Address to New York Stock Exchange, Tapes of Telephone Conversations and Meetings held by the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library, and photographs of Martin from the Missouri History Museum.

Martin collection in 2011, available from the Wayback Machine at https://web.archive.org/web/20110530074253/http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/martin/sources.php

Martin collection item in 2011, available from the Wayback Machine at https://web.archive.org/web/20110727192003/http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/martin/record.php?collection_references_id=4688

The process of reviewing, selecting, and describing individual items was time consuming. And in the end, the collection on FRASER was a selection of what FRASER librarians felt was important rather than a true reflection of the record.

personal papers

n.~ Documents created, acquired, or received by an individual in the course of his or her affairs and preserved in their original order (if such order exists).

https://www2.archivists.org/glossary/terms/p/personal-papers

Recently, we revisited this collection, applying our evolved standards that we developed for processing our other archival collections over the last decade. Series containing content predominantly in the public domain were digitized completely,[4] and PDFs corresponding to each archival folder in the physical collection were created, giving a better representation of the original order of the papers. The guiding question behind our selection of series was, “Will we be able to post all or most of the series on FRASER?” As with other files on FRASER, if pages were omitted from a PDF because of copyright or privacy issues, a note was inserted in the digital file to explain what was removed and why.[5] Descriptive information was compiled primarily from the folder titles, which had already been compiled in a finding aid prepared by the Missouri History Museum, thus reducing the time-consuming and subjective decisions needed by FRASER staff in creating descriptions. Although we scanned and processed as many pages as in the first phase, our second phase went much, much faster and was truer to the physical collection.

Martin collection in 2018, available at https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/archival/1341

As we proceed with the digitization of “new” archival collections, we are applying the MPLP principles. Selection is done only on a broad level. Digital files are created to correspond to physical folders, and metadata is taken primarily from the finding aid and/or box and folder labels. To provide another method of access, and to better convey to researchers exactly what is and is not available online, hyperlinks are added to the collection finding aids and made available on FRASER along with the collection, as we have done with the Martin Papers finding aid. If individual pages or items are redacted, they are replaced with a citation including the reason the item was redacted. With these methods, we give researchers a better representation of the physical collection while being transparent about what is and isn’t available digitally. And we do so in a more efficient manner, enabling us to make more digitized materials available to people all over the world.

[1] This quote is often attributed to Voltaire. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perfect_is_the_enemy_of_good

[2] This phrase was popularized by Mark Greene and Dennis Meissner in their seminal article More Product, Less Process: Revamping Traditional Archival Processing, published in The American Archivist: September 2005, Vol. 68, No. 2, pp. 208-263.

[3] Martin served as Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System from 1951-70, the longest serving Federal Reserve Chairman. Prior to that, he served as Assistant Secretary of the Treasury, President of the Export-Import Bank of Washington, and President of the New York Stock Exchange.

[4] The initial scanning project consisted of approximately 11,000 pages, and the second scanning project consisted of approximately 11,000 pages from Series IV, The Treasury Years and Series V, The Federal Reserve Board Years. The two projects contained significant overlap. In 2018, the total digitized content amounts to approximately 13,000 pages.

[5] See “About FRASER” for additional information on how we handle items with copyright or confidential markings.

The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.