With coin shortages and cryptocurrencies in the news recently, Americans may be thinking about the future of currency as they pull out cash or sort through a jar of change. Even so, a dive into FRASER yields an important revelation: Just as coins and currency can provoke thoughts about the future, they also can inspire learning about the past. This post explores the history of women on American currency.

Paper Currency

Other than figures of national personification—such as Lady Liberty and Columbia—the first woman in U.S. history to receive major depiction on currency issued by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing was Martha Washington. Her portrait appeared on the 1886 and 1891 series of one-dollar silver certificates. To date, Washington remains the only woman honored on our paper currency. Her likeness was again used, next to her husband George, on the reverse (back) of the one-dollar note of 1896, part of the famous “Educational Series” of silver certificates.[1]

Coinage

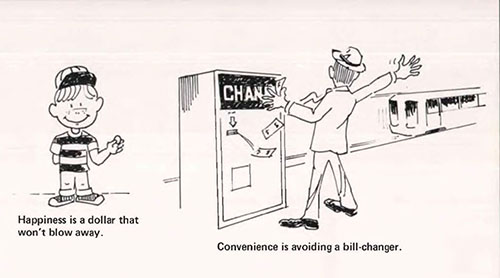

In October 1978, Congress passed Public Law 95-447. President Carter signed it into law. This legislation authorized the likeness of Susan B. Anthony to become the first portrayal of an actual woman—rather than an allegorical one—on a circulating U.S. coin.[2] The dollar coin was released to the public on Monday, July 2, 1979, with high expectations from the Department of the Treasury. Branded by the Treasury’s Bureau of the Mint as “the dollar of the future,” the coin was intended to offer numerous benefits over the dollar bill to consumers, retail businesses, and financial institutions, ranging from speedier cash handling to easier handling for children (thus less likely to be lost). Savings for American taxpayers were also an expected benefit of the coin’s adoption, given the substantially greater durability of coins over bills.

Unfortunately, the Susan B. Anthony dollar failed to win popular acceptance by American consumers. The U.S. Postal Service even intervened in early 1980 to encourage use of the dollar coin by increasing its appearance in change at post offices, but the coin failed to replace the dollar bill. A common explanation for the failure of the Susan B. Anthony dollar is that it bore too much resemblance to a quarter, hindering quick everyday transactions. Closer examination, however, raises uncertainty about this as the full explanation. For example, scholars John P. Caskey and Simon St. Laurent point out that “the Anthony dollar weighs 43 percent more than the quarter, has almost the same size relation to the quarter that the quarter has to the nickel, and has distinctly different engraving than the quarter,” suggesting other factors may have contributed to the Anthony dollar’s failure.[3] Caskey and St. Laurent attribute the failure to “network externalities,” explaining that “an individual who doubts that a new coin will become widely used by others will see little to gain from adjusting to use the coin.”[4] Consequently, owners of vending machines “can increase sales from converting their machines to accept the coin, but only if the public commonly carries the coin. Similarly, retailers who learn to distinguish quickly the new coin can make small transactions more rapidly, but only if their customers have also learned to distinguish the coin quickly.”[5] In other words, the benefits of the Anthony dollar coin would only be realized if enough Americans believed that their fellow citizens would use the coin widely and acted accordingly by using it themselves. When made to compete against the much more widely recognizable dollar bill, the Anthony dollar coin struggled to take off, earning it the nickname “Susan B. Edsel,” after a Ford automobile brand synonymous with failure.[6]

Despite the Susan B. Anthony dollar coin’s widespread failure to circulate in 1979-1980, the U.S. Mint again attempted introducing a dollar coin into circulation from 2000 to 2008, after a 1999 revival of the Anthony dollar.[7] This time, it was the Sacagawea “golden” dollar, so called due to its outer layer of manganese brass. The U.S. Mint involved officials from the American Numismatic Society and Smithsonian Institution, representatives from the Native American community, historians, and others to think through the coin’s design. A design produced by sculptor Glenna Goodacre was unveiled on May 4, 1999, at the White House.[8] In 2009, the obverse (front) of the Sacagawea dollar was absorbed into the Native American $1 Coin Program, which has introduced a new coin reverse each year since. The program’s collectible pieces are authorized as legal tender but are not intended for circulation.[9] Two years earlier, in 2007, U.S. Mint releases included a series of 24-karat gold coins depicting the first spouses of the United States.[10]

Beginning in 2022 and through 2025, significant women in U.S. history will be honored on coinage through the American Women Quarters Program, authorized by the Circulating Collectible Coin Redesign Act of 2020.[11] Previously, Helen Keller appeared on the Alabama state quarter released in 2003.[12] Quarters already released in 2022 feature Maya Angelou, Sally Ride, and Wilma Mankiller, and those to be released later in the year will feature Nina Otero-Warren and Anna May Wong.[13] The obverse of the current and future quarters in the series will feature George Washington and use a 1932 design by sculptor Laura Gardin Fraser.[14]

From the silver certificates of the late nineteenth century to the brand-new quarters of today, women’s representation on American currency has until recently been sparse. However, their contributions to national life have much to teach us about American history as a whole and can inspire us to build a future in which all talent is recognized, no matter the source.

[1] Kim Carter and Andy Young. “Uncurrent Events: Women of the Treasury, Past and Present.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Inside FRASER Blog, 2022. See also George Washington’s Mount Vernon. “Martha on $1.”

[2] See Cody White. “The Susan B. Anthony Dollar Coin – the Dollar of the Future?” National Archives and Records Administration Text Message, July 19, 2016. See also U.S. Mint. “Susan B. Anthony Dollar.” Content last reviewed March 4, 2022.

[3] John Caskey and Simon St. Laurent. “The Susan B. Anthony Dollar and the Theory of Coin/Note Substitutions.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, August 1994: 501.

[4] Caskey and St. Laurent (1994: 496).

[5] Caskey and St. Laurent (1994: 496).

[6] Caskey and St. Laurent (1994: 495). See also Tom Dicke. “The Edsel: Forty Years as a Symbol of Failure.” Journal of Popular Culture, June 2010: 486.

[7] See U.S. Mint. “Susan B. Anthony Dollar.”

[8] See U.S. Mint. “Sacagawea Golden Dollar Coin.” Content last reviewed February 22, 2021.

[9] See U.S. Mint. “Native American $1 Coin Program.” Content last updated January 31, 2022.

[10] See U.S. Mint. “United States Mint Offers First Spouse Coins.” May 10, 2007. See also U.S. Mint. “First Spouse Gold Coin Program.” Content last updated July 28, 2020.

[11] See U.S. Mint. “American Women Quarters™ Program.” Content last updated April 1, 2022.

[12] See U.S. Mint. “Alabama State Quarter.” Content last reviewed June 1, 2016.

[13] See U.S. Mint. “American Women Quarters™ Program.”

[14] See U.S. Mint. “American Women Quarters™ Program.”

© 2022, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.