FRASER has recently added 452 volumes of press releases, digitized from a collection in the U.S. Department of the Treasury library. Consisting of about 40,000 releases, the collection begins in 1916, right before the United States entered World War I, and ends in 2009 with the Treasury’s efforts to deal with the Financial Crisis of 2007-09. The releases document the events that helped shape modern American economic policy. The full FRASER collection for the Treasury includes statements and speeches from Treasury officials, data releases, policy documents, and more. The collection will continue to expand as the FRASER team works to capture “born-digital” Treasury releases from 2009 to the present. Here we highlight releases surrounding notable events in the Treasury’s history in order to show the research value that the extensive collection provides.

World War I and Liberty Bonds

- Treasury Secretary McAdoo Warns Against Early Selling of Liberty Loan Bonds, December 10, 1917 (Volume 1, PDF page 3)

On April 6, 1917, the United States entered World War I, which had begun in Europe in 1914. To finance U.S. military involvement, the federal government decided to sell short-term securities known as Liberty Bonds to the public. It was the first time most members of the general public were introduced to the idea of purchasing securities,[1] and purchases were strongly encouraged through a publicity campaign that stressed imperative patriotism. In a late-1917 press release, then-Treasury Secretary W.G. McAdoo is quoted as urging the citizens of America to not sell Liberty Bonds before their maturation date. He compares those who would sell their bonds early to the enemies of the United States: “Some persons sell these bonds for malevolent reasons. Investigations that I have made recently convince me that the hand of the Kaiser is behind certain sales.”

The Great Depression

- Statement by Secretary Mellon, December 31, 1929 (Volume 6, PDF page 260)

- Ogden L. Mills Speech to the American Association of Advertising Agencies, May 15, 1930 (Volume 6, PDF page 327)

October 29, 1929, also known as Black Tuesday, marked a critical moment in the history of the Great Depression, as the stock market crashed with reverberating effects for the U.S. financial system. In the aftermath, Treasury Secretary Andrew W. Mellon tried to assuage fears that the shock of the crash and the subsequent downturn in the economy would last. In a December 31, 1929, press statement, Mellon said:

I see nothing, however, in the present situation that is either menacing or warrants pessimism. During the winter months there may be some slackness or unemployment, but hardly more than is usual at this season each year. I have every confidence that there will be a revival of activity in the spring and that during the coming year the country will make steady progress.

However, by spring of 1930, as the economy failed to pick back up, it became harder for Mellon and Treasury Undersecretary Ogden L. Mills to keep as positive an outlook. In a speech at the Annual Dinner Meeting of the American Association of Advertising Agencies, Mills presented a much dourer forecast than Mellon had just three months earlier: “At the present time we are unquestionably passing through one of those depressions which, in spite of all our advances in business and economic science, seem to recur periodically.”

Pearl Harbor, World War II, and the War Loan Drives

- “The Job Ahead,” Secretary Morgenthau Speech, January 4, 1942 (Volume 39, PDF page 164)

- Secretary Morgenthau Commissions Walt Disney to Create Donald Duck Film, January 23, 1942 (Volume 39, PDF page 359)

- Announcement of Third War Loan Drive, August 19, 1943 (Volume 48, PDF page 106)

- Fifth War Loan Drive Radio Broadcast, June 12, 1944 (Volume 54, PDF page 125)

On December 7, 1941, the attack on Pearl Harbor brought the United States into the world war that had been raging since 1939. As it had in World War I, the Treasury relied heavily on sales of bonds to the public to help fund the new war effort. In a speech delivered over radio just under a month after Pearl Harbor, Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau acknowledges the “grand response” from Americans, who had purchased over $500 million in Defense Bonds in December 1940 alone, twice as much as the average for the previous seven months. He noted that in some places the demand for Defense Bonds was so high that the Treasury could not print them fast enough.

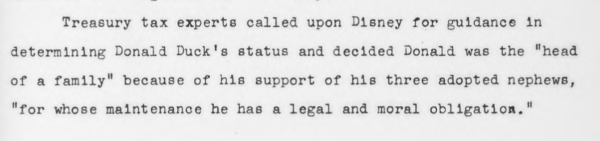

However, Defense Bonds alone could not fund the war effort. The Treasury counted on Americans to pay their federal income tax. To help encourage Americans to file their taxes, Morgenthau enlisted the services of Walt Disney to create a short animated film to show taxpayers how to file their taxes and how these funds would aid the war effort. The film, “The New Spirit,” features the Disney character Donald Duck, who learns that filing his income taxes is the best way to support the war effort and that, because he earned less than $3,000 the previous year, he is able to use a streamlined form for filing.

Clip from “Press Releases of the United States Department of Treasury,” Volume 39, PDF page 359

The movie was a success for the Treasury and the war effort, with reports of more than twice the number of income tax filings as the previous year.[2] The film eventually was nominated for an Oscar in the Documentary category of the 1943 Academy Awards.[3] The film’s success led the Treasury to enlist other popular figures to help raise war funds. For its Third War Loan drive, the Treasury announced that it would be using “the most glamorous salesmen in America”—Hollywood stars—to help boost sales of Defense Bonds. Among the actors drafted to help in this effort were Judy Garland, Mickey Rooney, Joan Crawford, and Cary Grant. Later, for the Fifth War Loan drive, the Treasury enlisted Orson Welles to help direct and narrate a radio play that featured Morgenthau and President Roosevelt and outlined the goals of the war bond effort. In all, the war bond campaigns raised a total of $185.7 billion in nominal currency for the Treasury.

Groundbreaking Women at the Treasury

- Mint Releases Franklin Half Dollar, January 7, 1948 (Volume 71, PDF page 28)

- Nellie Tayloe Ross Sworn in for Fourth Term as Director of the Mint, April 30, 1948 (Volume 72, PDF page 311)

- Georgia Neese Clark Sworn in as Treasurer of the United States, June 21, 1949 (Volume 78, PDF page 235)

- Azie T. Morton Sworn in as Treasurer of the United States, September 6, 1977 (Volume 208, PDF page 250)

On May 3, 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Nellie Tayloe Ross as director of the U.S. Mint. Ross, the first woman to hold the position, had previously served as governor of Wyoming from 1925-1927, the first female governor in the United States. During her tenure at the U.S. Mint, she established the Franklin half dollar and re-established the practice of making proof coins for public sale.[4] In 1948, on the occasion of Ross starting her fourth term in the position, the Treasury issued a press release describing her position and history as director. Ross served five full terms and retired in 1953.

Georgia Neese Clark became the first woman Treasurer of the United States, appointed by Harry S. Truman in 1949 and unanimously confirmed by the Senate.[5] The Treasurer is a key officer in the Department of the Treasury, which is responsible for the U.S. Mint, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, and is an important liaison with the Federal Reserve.[6] Upon her swearing in, Clark commented that her appointment “is more significant as a milestone in the advancement of women generally in National affairs. I hope very sincerely that it will encourage women everywhere to become still more interested, and more active, in public life.” Clark served in that position until 1953.

Nearly 30 years later, Azie T. Morton became the first African American Treasurer of the United States. Her work at the Treasury was preceded by many years of public service, including service on President John F. Kennedy’s Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity from 1961-1963. Morton was sworn in as Treasurer on September 12, 1977, and served in that role in the Carter administration until January 1981.

Currency Updates

- Secretary Mellon Announces New Small-Size Currency, June 3, 1929 (Volume 6, PDF page 155)

- United States Mint Develops Nickel-less Nickel, January 22, 1942 (Volume 39, PDF page 356)

- Treasury and Federal Reserve Announce New Currency Design, September 27, 1995 (Volume 353, PDF page 294)

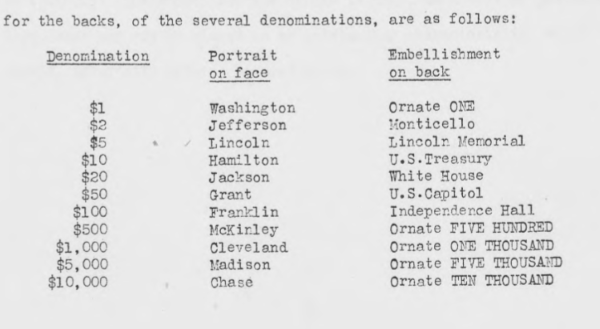

In 1929, Treasury Secretary Mellon announced the release of a new, reduced-size paper currency for the public. The redesign was an attempt by the Treasury to not only cut costs, but also standardize currency to fight counterfeiting. Each denomination of currency now had a uniform design, which was documented in the release announcing the currency roll out. The currency designs listed range from the $1 with George Washington’s portrait to the $10,000 bill—the largest denomination of currency ever publicly circulated—featuring Abraham Lincoln’s Treasury secretary Salmon P. Chase.

Clip from “Press Releases of the United States Department of Treasury,” Volume 6, PDF page 155

Later, during World War II, nickel and copper—two metal alloys present in the U.S. 5-cent (nickel) coin—became a high-demand resource. Scientists at the U.S. Mint set about trying to find an alternative alloy for use in the nickel coin. In a 1942 release, Ross announced that the Mint had successfully developed a new nickel coin made up of 50 percent copper and 50 percent silver. The innovation would end up saving the United States crucial materials for the war effort but still be functional in the coin-operated machines of the time.

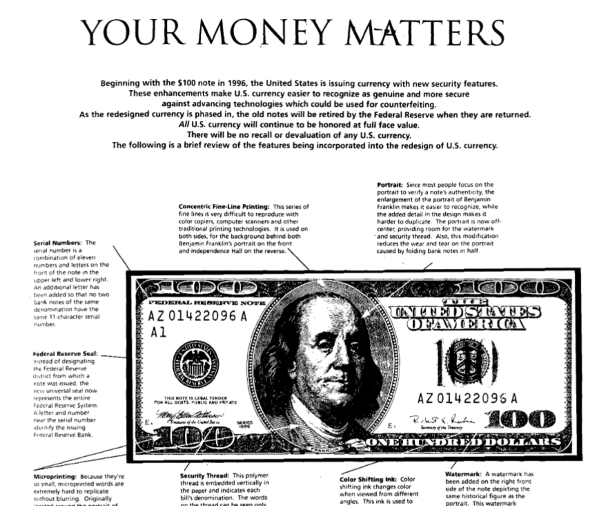

Further changes to U.S. currency happened in response to technological innovations in 1990s. As digital photoduplication technology became better and cheaper, currency needed new safeguards to protect against counterfeiting. In 1995 the Treasury announced the release of a new $100 bill note that incorporated new and modified security features to deter counterfeiters. The reissue was the first major redesign of the $100 bill since its standardization in 1929 and included ultraviolet ink watermarks, color-shifting ink, and microprinted text.

Image from “Your Money Matters” in “Press Releases of the United States Department of Treasury,” Volume 353, PDF page 321

This selection of press releases represents only a fraction of the the total historical collection from the Treasury. To better understand the full scope of the collection, users are encouraged to also explore the indexes of the volumes of Treasury materials released between 1941 and 2004.The full collection touches on a wide range of major events in U.S. economic history in the 20th and 21st centuries and will continue to grow to incorporate current events.

[1] O’Sullivan, Mary. “The Expansion of the U.S. Stock Market, 1885-1930: Historical Facts and Theoretical Fashions.” Enterprise & Society, September 2007, 8(3).

[2] Jones, Carolyn C. “Class Tax to Mass Tax: The Role of Propaganda in the Expansion of the Income Tax during World War II.” Buffalo Law Review, October 1, 1988.

[3] Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. “The 15th Academy Awards.” 1943.

[4] Kansas Public Radio Staff. “Female Firsts – April 24, 2015.” Kansas Public Radio Blog, April 24, 2015.

[5] Saxon, Wolfgang. “Georgia Neese Clark Gray, 95, First Woman as U.S. Treasurer.” New York Times, October 28, 1995.

© 2020, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.