As many schools and universities move to online learning in response to the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak, FRASER hopes these historical primary and secondary source resources from our collection and those of our partners and colleagues will be useful.

Economic (and other) Data

- FRED® data with the keyword “health“: These data include healthcare price indexes, personal and industry expenditures, and more.

- FRED data: Federal and state/local government investments in hospital buildings, 1901-1996

- The FRED Blog: “The economic impact of a pandemic” looks at the effects of the 1918 influenza outbreak (commonly known as the “Spanish flu“) on wages in the U.S.

- The FRED Blog: “The Black Death in the Malthusian economy” explores population and earnings data during the bubonic plague of the 14th century.

- FRED Blog posts with the keyword “health“: Some include GeoFRED® maps with state and county comparisons.

- New FRED dashboards to monitor the economy

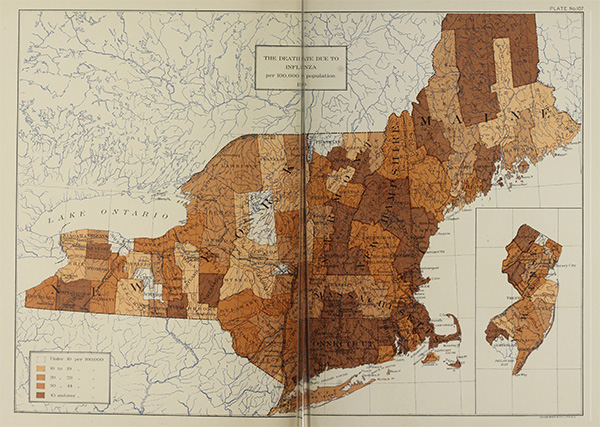

“The Death Rate Due to Influenza per 100,000 Population” in the Statistical Atlas of 1900.

- Statistical atlases: This series of volumes illustrates Census Bureau data, with various data on common causes of death. In the early years, only certain areas of the country (like the Northeast, pictured here in an illustration from 1900) kept regular mortality statistics.

- The 1870 and 1880 atlases include various approximate mortality statistics covering medical and other causes of death.

- As in earlier years, pneumonia was included in the mortality statistics of the 1890 atlas but not influenza, despite the 1889-1890 outbreak of “Russian flu.”

- The 1900 atlas shows influenza and pneumonia death rates[1] as well as those of other major illnesses of the time.

- The 1910 atlas includes statistics for more areas but fewer illustrations and less data overall.

- Following the 1970 decennial census, the U.S. Geological Survey published a National Atlas of the United States of America that includes this chart of death rates for selected causes from 1915-1970.

- The Bureau of Labor Statistics published a number of studies in the early 20th century covering workplace mortality and “causes of death by occupation” and vital statistics of major U.S. cities. A 1930 report noted influenza deaths were particularly prevalent among coal miners, “iron-foundry workers, furniture and other wood workers, cigar makers and tobacco workers, and iron and steel mill workers.”

The 1918 Influenza Pandemic

Overview and Data Sources

- From the second quarter 2019 Richmond Fed Econ Focus: “All the City Was Dying: The Spanish Flu Pandemic of 1918-1919 Was a Major Social and Economic Shock”

- From the March 2008 Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review: “Pandemic Economics: The 1918 Influenza and Its Modern-Day Implications.” This article by Thomas A. Garrett provides “an overview of the influenza pandemic of 1918 in the United States, its economic effects, and its implications for a modern-day pandemic.” His dataset is partially sourced from historical newspapers. Garrett, a former St. Louis Fed economist, also wrote a working paper (a preliminary research paper not yet formally published; common in economics and other fields) on how World War I and the influenza pandemic affected wages in the manufacturing sector.

- A curated primary source set from the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA): “America during the 1918 Influenza Pandemic”

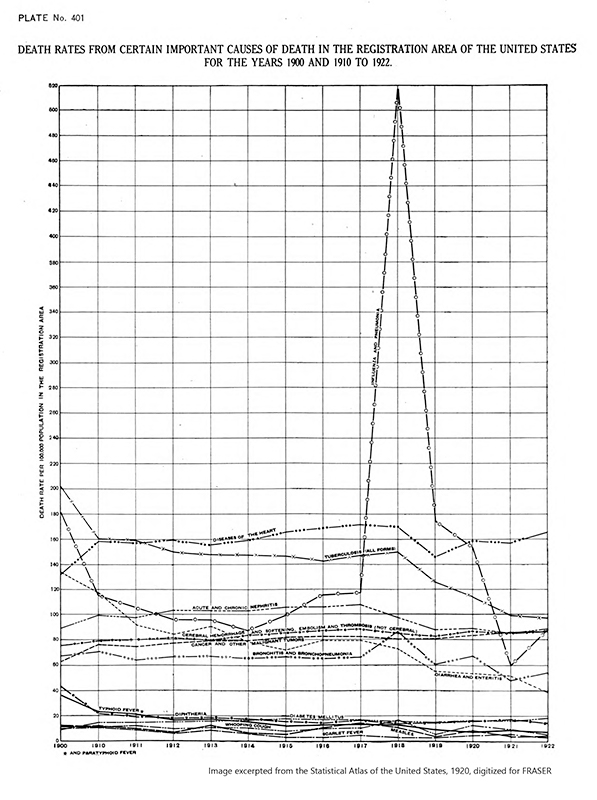

- From the 1920 Statistical Atlas of the U.S. (the last regularly produced of its kind): This striking chart is of influenza deaths from 1910-1920.

“Death rates from certain important causes of death in the registration area of the United States for the years 1900 and 1910 to 1922.” The sharp spike shows the rate of influenza and pneumonia deaths.

The Data in Context

The 1918 influenza pandemic began as World War I was drawing to a close. The Federal Reserve, which had opened in November of 1914, helped steer the country through its shift to a wartime economy.

The earliest cases of the new influenza strain appeared in March 1918 and traveled the world with the American soldiers heading off to fight in the war, helping turn an epidemic into a pandemic.[2] The flu spread quickly across the U.S., but the severity of the outbreak was not yet clear. In late September, the Commercial and Financial Chronicle business newspaper said that “an epidemic of Spanish influenza has checked business to some extent, but is not expected to be lasting. The Department of Health of this city [New York] has just voted $25,000 to fight influenza, which it calls pneumonia in epidemic form. It is said to be in reality the old-fashioned grippe.”

In early October 1918, the Commercial and Financial Chronicle reported that the flu had affected “camps, munition plants, shipyards and colleges” and had “invaded 36 of our 48 states.” The October 5 and 12 issues discussed which businesses were being closed and where, what measures were being taken to reduce crowding and contagion, and whether other cities should follow suit. In the 1910s, physicians and policymakers were unclear on the specific causes of many deadly diseases, and standards for healthy living and working conditions were still being developed across the country. Employers provided facilities with the newest accommodations, such as clean, nearby toilets and good ventilation and lighting, to some workers much earlier than others.

The pandemic continued to move quickly. By mid-October, the Fed’s Board of Governors (then a much smaller entity called the Federal Reserve Board) saw the uptick in influenza and recommended staff inoculation against the flu. Documents from the papers of the Department of Labor’s Women’s Bureau from late October 1918 show that one laundry service contracted by the military base hospital at Ft. Oglethorpe in Tennessee had such a high volume of work due to the influenza outbreak that the War Department suspended the workers’ “Day of Rest” law.

In 1918, up-to-date, comprehensive economic data were as sparse as workplace standards. Measures of gross domestic product, the national unemployment rate, and many other major economic indicators were years or decades away. To better assess the condition of the U.S. economy, each of the Federal Reserve Banks provided monthly reports (resembling those in today’s Beige Book) on the economic conditions of their regional Districts that were compiled in the monthly Federal Reserve Bulletin.

In November 1918, the month World War I ended, nearly every District’s report (except those for the Minneapolis and San Francisco Feds) in the Bulletin mentioned the influenza outbreak. The New York Fed reported profits decreasing in “almost every line of industry” partially due to influenza and the military draft’s drain on the labor force but said the situation was less severe than in other Districts. Other Fed Districts mentioned significant flu mortality and labor shortages in the coal mining industry,[3] which caused supply shortages in manufacturing. The city of St. Louis had taken swift action in October in response to the outbreak, and the St. Louis Fed reported the following on the response of the local economy:

Reports from other Federal Reserve Banks indicated the flu outbreak affected retail trade across the board: The Philadelphia Fed reported that “as many as one-third of the [retail] employees have been unfit for duty.” In a retrospective report in December, the San Francisco Fed noted that the “compulsory wearing of gauze masks,” which had reduced new cases of influenza from 2,304 on October 25 to 75 on November 13, interfered with not only retail sales but also distribution and wholesale stocks.

Influenza affected other sectors as well. According to the Department’s 1918 annual report (published in December), more than 1,000 employees of the U.S. Treasury Department in Washington, D.C., had contracted the flu that year. In response, the “women of the Treasury Red Cross Auxiliary and the other employees of the department” provided medical services and opened an emergency kitchen to feed their colleagues, under the direction of the Public Health Service. On December 14, the Commercial and Financial Chronicle reported significant losses for the railroad industry, a downturn in cotton orders, and even a decline in “electric railway” (subway or public transit) and utilities earnings “due to quarantine regulations.” The New York Department of Labor’s December summary in that paper noted October downturns in “all of the eleven industry groups… [but the] heaviest in the paper and textile trades” due to the pandemic.

By the time the December 1918 Federal Reserve Bulletin published, the economic effects seemed to be waning. The Atlanta Fed reported that month that the influenza had shut “about 30 coal mines” in October but “within the next 10 to 15 days” conditions were expected to return to normal. Economic activity improved, but the impact was not soon forgotten. In February 1919, the prior year was described as “the most extraordinary in the history of life insurance” in the Commercial and Financial Chronicle. One insurance company announced that “of the $27,799,026 distributed in death claims by the Equitable [Life Assurance Society of the United States] in 1918, $5,200,000 was directly due to the influenza and pneumonia epidemic.”

In April 1919, as the economy began to downshift from the boom of war production and recover from the shock of the pandemic, President Wilson proposed a “New Plan of Price Stabilization” intended to “address post-war stagnation in commerce and industry.” The overview given in the Bulletin included answers to public concerns about the disruption that government influence on industries would cause:

The distribution and allocation of labor to war industries has upset the normal pattern in this country for four years. What is proposed is a stimulated peace industry which will employ as much or more labor as did war industries—especially considering the loss of man power, due to decreased immigration, loss by influenza, war, and probably increased Army and Navy. That it will employ them in different places and at different tasks is inevitable, whether the proposed step is taken or not.

By the time flu season rolled around again in fall 1919, the country had made additional preparations for a new outbreak. The St. Louis Fed reported this in September:

Drug concerns report increases in business as high as 25 per cent over July last year. One concern says it has larger orders on hand for future delivery than are usual at this time of the year. It attributes this fact largely to the expected return of the influenza epidemic this fall. Stocks in the hands of retailers are said to be larger and more complete than formerly.

Public Health and the Economy Since 1918

Federal Reserve Discussion of Epidemics and Pandemics

Like many other factors affecting the economy (from conflicts to international trade to weather), epidemics and pandemics are noted and discussed by the economists and policymakers of the Federal Reserve.

- As in 1918, later flu outbreaks have shown up in the Federal Reserve Bulletin.

- From November 1957: “[Widespread influenza in September-October 1957 is] probably contributing to the decline [in retail sales]…Seasonally adjusted retail sales declined 2 percent in October. The decrease, which was fairly general, apparently was influenced by the incidence of Asian influenza. Sales at food stores and automotive outlets changed little. At department stores, sales declined substantially in October, but were recovering in early November.”

The 1957 influenza outbreak was of moderate severity,[4] and the Board of Governors recommended vaccination against the flu for much of the staff.

- Since its first meeting in March 1936, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) has often discussed unexpected influences on the U.S. and global economies, including influenza and other epidemics.

- Memorandums of discussion (a precursor to today’s meeting transcripts) from the January and March 1969 FOMC meetings mention the mild4 influenza outbreak of the prior fall. From the January meeting: “Retail sales had rebounded in November but had failed to return to the August high, and then had dipped significantly in December. The extent to which that dip was related to the Hong Kong flu was debatable.”[5]

- The May 2003 FOMC meeting transcript captures a discussion of the newly emerged threat of SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) and its possible economic effects:

One new element in the global economic picture since your March meeting has been the emergence of SARS as a major economic threat to most of the emerging Asia region. Even though we have no expertise in anticipating the course of the disease, construction of the Greenbook baseline forecast required that we make a set of working assumptions about its implications for economic activity.

Chairman Greenspan included SARS in his testimony on the economic outlook to the Joint Economic Committee later that month.

- The June 2003 FOMC meeting mentioned “the restraining effect of SARS on retail purchases of IT products by consumers in mainland China” felt in the San Francisco Fed District.

- The June 2009 FOMC discussion of H1N1 influenza centered on the shock to the Mexican economy (hard-hit but recovering).

Discussion on Preparedness

Epidemics and disaster preparedness have been covered by a variety of Fed and government economic information sources.

- This 2006 Dallas Fed circular discusses influenza pandemic preparedness for the financial industry.

- The U.S. budget for fiscal year 2007 includes funds for pandemic influenza preparation.

- Effects on the pork production industry from the 2009 H1N1, or “swine flu,” outbreak were reported in the Richmond Fed’s Econ Focus that fall.

- The August 2009 “Mid-Session Review of the [U.S.] Budget” included “additional emergency funding related to the H1N1 influenza virus.”

Other Resources

These and many other historical sources can be found with a simple keyword search on FRASER, but teachers, students, and researchers are always welcome to contact a FRASER librarian for help. For information about the Fed’s response to the 2020 coronavirus outbreak, go to federalreserve.gov/covid-19.htm.

[1] For an explanation of early mortality statistics in the U.S., see the following: Thomas Ewing. “La Grippe or Russian Influenza: Mortality Statistics During the 1890 Epidemic in Indiana.” Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses, May 2019, 13(3), pp. 279-287.

[2] American College of Emergency Physicians. “1918 Influenza Pandemic: A United States Timeline.”

[3] Later, the Board of Governors also reported a significant decline in gold mining attributable to the “shortage of the labor supply, high cost of materials, and the prevalence of the influenza” in 1918.

[4] Andrew Burns, Dominique van der Mensbrugghe, and Hans Timmer. “Evaluating the Economic Consequences of Avian Influenza.” World Bank Working Paper, June 2006. The authors classify the 1918 flu as their “severe” sample case.

[5] This flu outbreak is also mentioned briefly in the February and March 1969 New York monthly Review and in the January 1969 Survey of Current Business.

© 2020, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.