Next year, in 2020, the Department of Labor’s Women’s Bureau will celebrate 100 years of studying women in the workforce. Since 1920, the director of the Women’s Bureau has been a woman; in fact, the act[1] establishing the bureau mandates that the bureau “shall be in charge of a director, a woman.”

Mary Anderson, the first director of the Women’s Bureau, led the bureau for almost 25 years, from 1920 to 1944. Anderson’s contributions and accomplishments have been rightfully recognized and remembered.[2] Less known, perhaps, is that prior to becoming director of the Women’s Bureau, Mary Anderson was the assistant director of the Bureau’s lesser-known predecessor, the Woman in Industry Service (WIS), which was led by Mary Van Kleeck (pictured at left in a Library of Congress photo) through its brief 14-month existence. The WIS was one of the several new war-time divisions established by the Department of Labor. It was charged with maintaining contact with all other governmental divisions so that it could determine what labor issues were affecting working women, especially with regard to government contracts. In order to reveal the types of conditions women were enduring, the WIS worked with divisions such as the War Department and the Navy to conduct field investigations of war manufacturing plants.[3] Despite serving the Department of Labor for only a short time, Van Kleeck and her work set the foundation for what would become the Women’s Bureau and created labor standards that continue to be relevant today.

In 1791, long before the creation of the WIS in 1918, Alexander Hamilton acknowledged that women in the U.S. were an underutilized workforce population and encouraged them to participate in manufacturing industries.[4] And although women were involved in the labor force since the nation’s earliest days, their contributions, and presence, remained largely ignored.[5] Mary Van Kleeck, who had studied economics at Smith College and Columbia University,[6] was an early advocate for working women, including for a decade as the Director of the Division of Industrial Studies for the Russell Sage Foundation, an advocacy organization for the “improvement of social and living conditions in the United States.”[7] In this position, Van Kleeck led investigations and wrote reports that exposed poor working conditions affecting women. For example, one of her publications, on the artificial flower trade, exposed wage discrimination, poor workplace conditions, and the exploitation of the very poor through sweatshop and tenement “home work.” In this study, Van Kleeck emphasized that her sole focus was the well-being of the female workers. Her team scrutinized the companies’ practices by examining records, interviewing employers and employees, and conducting factory and home site visits.[8] Van Kleeck would later carry this dedication and expertise to her work with the WIS.

Despite calls early in the century for the Department of Labor to report on the “conditions of working women,” it was the changes in the labor force from World War I that made investigating those conditions a priority. In 1917, about a quarter million men a month[9] were leaving the labor force for military service. This drastic depletion of the nation’s labor force combined with the manufacturing demands of the war sparked new opportunities for women: Suddenly the country was relying “upon the work of women as the sole reserve force of labor.”[10] To meet the extraordinary labor needs, women entered industries they would not otherwise have been admitted to. War industries, in particular, were hiring women: The aircraft industry was one of the “first of the big war industries to bring [women] in in large numbers.” The Navy, munition plants, and Army camps also employed female workers, as did piano manufacturers, the railroad industry, motion picture theaters, and other civilian businesses.[11] Mary Van Kleeck began working for the women’s branch of the Ordnance Department of the U.S. government in January 1918.[12] This Department, responsible for providing the army with much needed war supplies, hired Van Kleeck to supervise the employment conditions of women working in manufacturing plants that held federal government contracts.

In July 1918, the Secretary of Labor announced that “Congress has now granted the necessary authority to establish a Women’s Division in the Department of Labor” (here, the “Women’s Division” refers to what would become the WIS). The secretary explained that,

At the time of the above announcement, the Secretary of Labor announced the appointment of Mary Van Kleeck as director and Mary Anderson as assistant director of the new WIS. Van Kleeck’s writings indicate she was acutely aware of the vast importance of the monumental task before them. In the September 15, 1918, Newsletter of the Woman’s Committee Council of National Defense, Van Kleeck declared that the creation of the WIS was a “recognition of the national importance of women’s work.” She also spoke of a “new freedom” for women: “freedom to serve their country through their industry not as women but as workers judged by the same standards and rewarded by the same recompense as men.” And though the division was primarily tasked with examining war conditions, in its first annual report, Van Kleeck and her largely female staff reflected that the work they were doing was “likely to have permanent social effects.“

To ensure thorough investigations, Van Kleeck instituted may of the techniques used while working for the Russell Sage Foundation. The WIS examiners conducted site visits, during which they gathered as much information as possible. They toured the area, collected documents (such as payrolls), and interviewed employers and employees. Through these investigations, the WIS uncovered insufficient working conditions and unfair practices: Women were working long hours in unsanitary conditions with hazardous materials and often for far less money than men who were doing the same work. Once this information was gathered, they produced internal reports that were submitted to Van Kleeck for final review. Many of the investigations that took place were done so at the request of others. For example, the governor of Indiana submitted a request that became the report “Labor Laws for Women in Industry in Indiana.” The WIS also studied wage discrimination and the cost of living for women and argued that pay should be “established on the basis of occupation and not on the basis of sex or race.”[13]

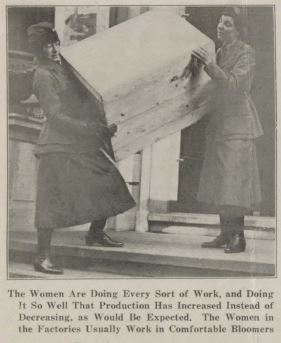

Image from a 1918 music trade publication clipping in the Mary Van Kleeck papers.

One of the most influential publications of the WIS was Standards for the Employment of Women in Industry, published in December 1918. These guidelines, informed by Van Kleeck’s investigative work, were later adapted into the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938,[14] benefiting all employees in the U.S.: The 1918 standards recommended that a women’s workday be limited to eight hours (and only four hours on Saturday plus “one day of rest in seven”), meal breaks be at least 30 minutes, and short rest periods be allowed without “increasing the length of the working day.” Today, the Wage and Hour Division of the Department of Labor similarly stipulates a maximum 40-hour work week unless overtime regulations are followed, meal breaks of “typically 30 minutes or more,” and short breaks that “must be counted as hours worked.”

When the armistice was signed on November 11, 1918, the WIS had been in existence for only four months. Even though the WIS was widely supported,[15] the division was in danger of being dissolved. Undeterred, Van Kleeck argued for the work of the WIS to continue, made plans for the future, and continuously urged for Congress to make the WIS a permanent division, to be known as the Women’s Bureau.

In July 1919, Van Kleeck resigned[16] as director of the WIS and left Washington to care for her dying mother.[17] If she had not left, Van Kleeck would have likely become the first director of the Women’s Bureau. She continued as an advocate for working women, including ongoing work at the Russell Sage Foundation, 20 years as an associate director of the International Industrial Relations Institute, and five years on the board of directors of the ACLU.[18] She was elected as a fellow of the American Statistical Association in 1945.[19]

Van Kleeck’s dedication, determination, and drive changed the way working women are viewed in this country. In her 1951 autobiography, first director Mary Anderson credited Van Kleeck with setting the pattern for the work of the Women’s Bureau.[20] Without her and the foundation she built, the Women’s Bureau might not have lasted this long. Next year, as we celebrate the Bureau’s centennial, let’s not forget to honor the tenacious Mary Van Kleeck—the woman-power behind the Woman in Industry Service.

[1] U.S. Congress. Public Law No. 259, 66th Congress, H.R. 13229. An Act to Establish in the Department of Labor a Bureau to be Known as the Women’s Bureau. June 5, 1920.

[2] U.S. Department of Labor,Women’s Bureau.”Our History: An Overview 1920-2012.”

[3] Mary Van Kleeck. “Conference of State Officials…State Labor Laws, Box 1, Folder 1.” Records of the Women’s Bureau, Record Group 86, 1918-1919: 88-89.

[4] Alexander Hamilton. “Report on the Subject of Manufactures,” in Official Reports on Publick Credit, a National Bank, Manufactures, and a Mint. William McKean, 1821: 176.

[5] Claudia Goldin. Understanding the Gender Gap: An Economic History of American Women. Oxford University Press, 1990: 186.

[6] Chris Nyland and Mark Rix. “Mary Abby Van Kleeck,” in A Biographical Dictionary of Women Economists, edited by Robert W. Dimand, Mary Ann Dimand, and Evelyn L. Forget. Edward Elgar Publishing, 2000.

[7] Russell Sage Foundation. History of the Russell Sage Foundation.

[8] Mary Van Kleeck. Artificial Flower Makers. New York, Survey Associates, INC., 1913: vi.

[9] Woman in Industry Service. “First Annual Report of the Director of the Woman in Industry Service.” Bulletin, 1919: 3.

[10] It is important to note that African American men and women were also joining the labor force at increasing numbers during WWI. (The WIS did include African American women in some of its research). For more information regarding African Americans during WWI, check out the Inside FRASER article “Staff Picks: The ‘Division of Negro Economics,’ 1918-1921.”

[11] To explore further industries hiring women, see Correspondence of the Director [Mary Van Kleeck], 1918-1920 and Records Relating to Women in World War I, 1918-1919.

[12] According to a statement given by Mary Van Kleeck on October 1, 1918, at a conference held by the War Labor Policies Board, the Ordnance Department was the first division in the federal government to organize a women’s branch (in January 1918).

[13] While the first federal government endorsement of “equal pay for equal work” was released in 1917, it wasn’t until the Equal Pay Act of 1963 that most companies, nationwide, were required to pay “employees of the opposite sex for equal work.”

[14] Although various state labor laws had come into being in the preceding few years, these were the first national labor standards.

[15] Indiana Governor James P. Goodrich is one example of the support the WIS received; he recommended a permanent division based on the report the WIS created for his state.

[16] Although Van Kleeck signed her resignation letter as “Director, Women’s Bureau,” legislation establishing the Bureau wasn’t passed until after her resignation, so she never officially held the position.

[17] “Mary van Kleeck Papers, 1849-1998.” Five College Archives & Manuscript Collections.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Journal of the American Statistical Association. “Minutes of the Annual Business Meeting.” March 1946: 84-87.

[20] Mary Anderson and Mary Winslow. Woman at Work: The Autobiography of Mary Anderson as Told to Mary Winslow. University of Minnesota Press, 1951: 135-136.

© 2019, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.

@FedFRASER

@FedFRASER