Over the past century, women experienced tremendous progress in the workforce: Consider, for example, women’s roles as dressmakers and seamstresses compared with their roles as members of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and presidents of Federal Reserve Banks.

From the 1920s through the 1950s, the Women’s Bureau (part of the Department of Labor) published case studies on the topic of women in the workforce. The case studies identified changes in the roles, progress, and status of women in the workforce. Not only were these publications focused on the work of women, many of the publications were written by women, including Women’s Bureau employees Caroline Manning, Mary-Elizabeth Pidgeon, and Harriet A. Byrne.

Caroline Manning

In “Wage-Earning Women and the Industrial Conditions of 1930: A Survey of South Bend,” Caroline Manning, the industrial supervisor of the Women’s Bureau, interviewed members of the South Bend and Mishawaka, Indiana community. Her goal was to document how women’s work changed as unemployment began to increase in the United States during the Great Depression. Manning interviewed women employees in their homes and employers in their work environments. In many instances, the employers “furnished pay-roll and other plan records that served as the best possible check upon the findings that resulted from the interviews.”

Her interviews revealed that, as overall unemployment began to rise, women began taking jobs previously only held by men, but for lower wages: “Skilled rubber-shoe makers were despondent over having lost their trade; machines that were revolutionizing the jobs had been introduced recently, and… they had seen women hired in their places at greatly decreased rates of pay.” Manning also surveyed local women to determine their changes in employment over the past five years. Many women were consistent and stable in their employment: “Almost two-thirds of the women had only one job during the five years under consideration, and slightly less than one-fourth had worked in two jobs only.”

Mary-Elizabeth Pidgeon

Mary-Elizabeth Pidgeon was an educator and political activist who campaigned for women’s suffrage. While working for the Women’s Bureau from 1928 to 1956, she sought to measure the changes in the number of women in the workforce. As she notes in “Trends in the Employment of Women, 1928-36,” “It is of importance to examine the extent to which increases in employment have affected women…and to ascertain to what extent women are advancing or receding as a proportion of all employed persons.”

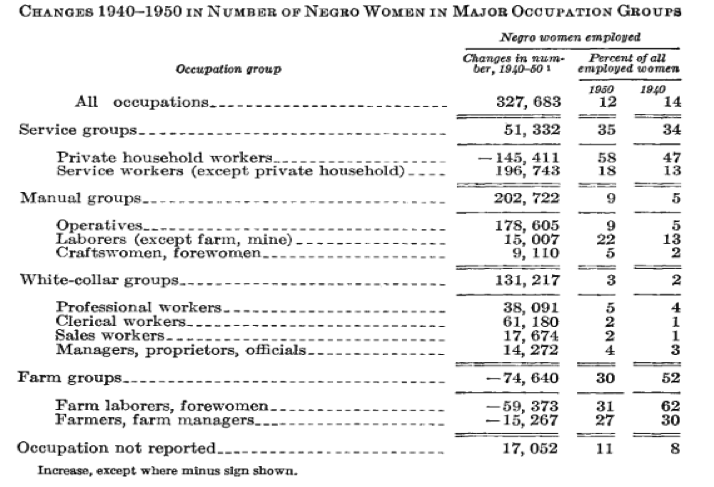

Pidgeon also wrote “Changes in Women’s Occupations, 1940-1950,” which measured women’s employment in several fields. In that report, she argued that “Occupational change is an indicator of the trends in women’s economic status. It also illustrates women’s current contribution and suggests their potential service in building and maintaining the strength of this country.”[1] Later in the report, she specifically identified the major occupation groups of Negro women, comparing the changes in their workforce participation over a decade: “The number of employed Negro women increased from 1940 to 1950 by a fifth.”[2] Increases were especially large for service workers and “operative” (mostly manufacturing) jobs, as illustrated in the chart:

Harriet A. Byrne

In the early 1930s, Harriet Byrne, an assistant editor at the Women’s Bureau, focused on women in business. She wrote two articles that specifically studied women’s roles in business fields: “The Age Factor as It Relates to Women in Business and the Professions” and “Women Who Work in Offices.” In the first, Byrne analyzed age, marital status, education, earnings, and work experience to better understand women’s obstacles in the working world. She interviewed women who experienced discrimination when seeking employment, preventing them from working in many fields:

A women of around 30 years, with 1 child and 2 adults dependent upon her, and living in a West North Central State, had taught school for 9 years before marriage. She had a bachelor’s degree in education, but since her marriage she had been able to secure only substitute teaching.[3]

Not all women found insurmountable barriers, though:

A single woman of 43 years, a graduate of a normal school but “hating” teaching had taken a business-college course. Through her work as stenographer she learned insurance selling, her vocation in much of the 18 years of her work history. Her earnings for 1930 were reported as $12,000.”[4]

In “Women Who Work in Offices,” Byrne studied a survey of 5,039 women office workers, which had been conducted at Young Women’s Christian Association clubs and camps throughout the country. Based on the survey responses, she was able to estimate the amount of schooling needed for a certain position: “About two-thirds of the clerks and almost nine-tenths of the cashiers or tellers reported attendance at high school their maximum schooling.”

Visit FRASER to read these or any of the other 200+ articles from the Women’s Bureau and its many woman writers, and learn more about the historical experience of women in the workforce.

[1] Women’s Bureau and Mary Elizabeth Pidgeon. “Changes in Women’s Occupations, 1940-1950.” Women’s Bureau Bulletin No. 253. 1954: 3.

[2] Women’s Bureau and Mary Elizabeth Pidgeon. “Changes in Women’s Occupations, 1940-1950.” Women’s Bureau Bulletin No. 253. 1954: 10.

[3] United States. Women’s Bureau and Byrne, Harriet A. (Harriet Anne), 1892-. The Age Factor as it Relates to Women in Business and the Professions : Women’s Bureau Bulletin, No. 117 , Washington: Govt. Print. Off., 1934: 10.

[4] Ibid., 62.

© 2018, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.

@FedFRASER

@FedFRASER