Because many discussions of women’s rights center around social or political rights such as the right to vote or hold office, you may not know that the right to participate in the economy has also changed and developed for women over time.

Some economic rights were available to women from the earliest years of the United States. The Patent Act of 1790 explicitly allowed women to hold patents, declaring that anyone could petition for a patent, “setting forth that he, she, or they hath” made an invention or discovery.[1] Throughout the history of the nation, some women worked for wages.[2] Although statistics are hard to come by, according to one study, approximately 15-20% of women in Philadelphia who were heads of household (generally widows) between 1790 and 1860 had documented professions.[3] Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton even wrote favorably in 1791 of how “women and children are rendered more useful…by manufacturing establishments, than they would otherwise be.”[4]

Although the government collected little data on women’s work and wages for most of the 19th century, we know that a growing number of women earned wages, held a wider variety of jobs, and exercised economic freedoms.[5] Across the country, laws shifted with societal attitudes about women’s public roles. Beginning in 1839,[6] married women began to be granted rights to retain their own property; before that the control and legal ownership of a woman’s assets generally passed to her husband upon marriage.[7] In 1847, the first law restricting women’s labor contracts was passed, when New Hampshire capped working hours for women in manufacturing at 10 hours a day.[8] With the passage of the 13th amendment and the end of the Civil War, black women entered the ranks of wage earners and began to negotiate their own wages and work contracts.[9] In 1862, California passed a law establishing women’s rights to bank under their own names, regardless of their marital status.[10] That same year, the Homestead Act allowed unmarried, divorced, or widowed women (including African Americans)[11] to homestead as head of a household.[12] In 1870, Virginia Woodhull, often lauded as America’s first female stockbroker, opened a brokerage house in New York. Although her institution was short-lived, two more women’s stock exchanges opened in 1880[13]—all made necessary because women were barred from the New York Stock Exchange (and would remain so until 1967).[14] By the 1880s, women’s labor force participation had expanded to the point where the 1890 census at last contained detailed statistics about women’s occupations.

In 1908, in Muller v. Oregon, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of laws restricting women’s hours and working conditions, largely based on (future Supreme Court Justice) Louis Brandeis’s legal brief, which asserted that “overwork” was medically bad for women and their ability to bear children.[15] The brief concluded that “it cannot be said that the Legislature of Oregon had no reasonable ground for believing that the public health, safety, or welfare did not require a legal limitation on women’s work.”[16] Following that precedent, laws protecting certain classes of working women proliferated in the early years of the 20th century. Even though women mobilized for their own protection and better working conditions, as in the 1909-1910 Shirtwaist Workers Strike,[17] the progress made was often due to the desire of lawmakers to protect women and their maternal capacity.[18] This protective trend encompassed the introduction of hour maximums, minimum wages, and state stipends to single-parent households.[19] Women’s property rights were also diminished in this era by state laws designating women’s inherited property to be family property (and therefore under control of her husband).[20]

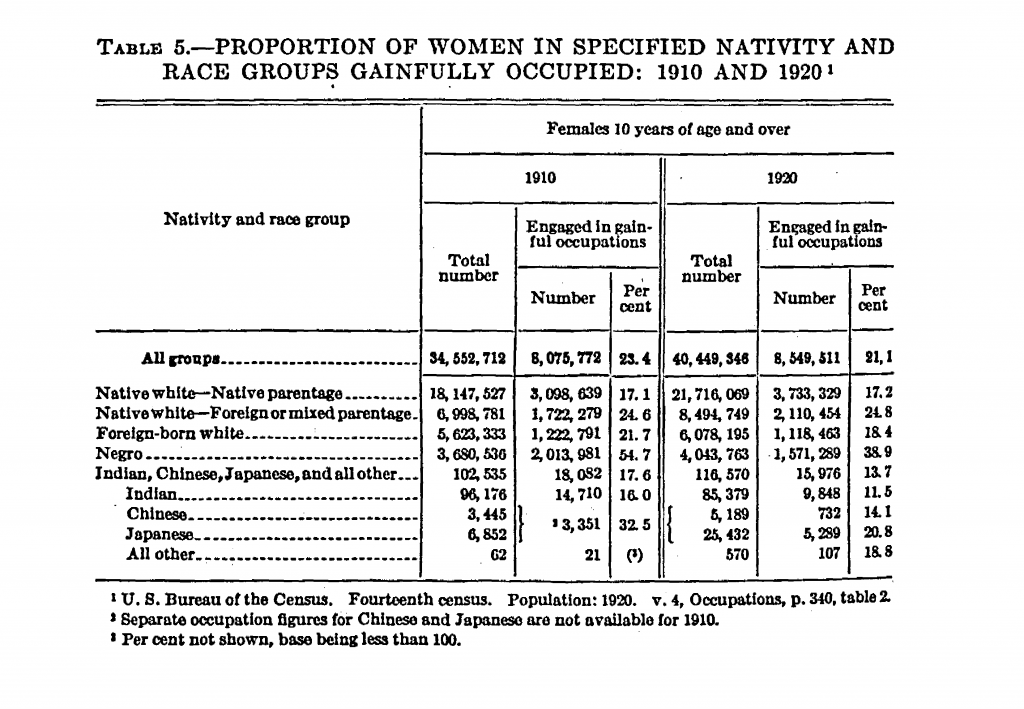

From the 1925 Women’s Bureau Bulletin, “Facts About Working Women.”

Women’s maximum-hours laws were used to push women out of certain industries, such as streetcar transportation and newspaper printing, where they competed with men with no such restrictions. Though the percentage of women working had risen steadily from 1890 to 1910, it fell between 1910 and 1920 for nearly all categories of women, possibly because of these constraints.[21] Women’s participation in the labor force also fell between the 1920 and 1930 censuses, but some of that change can be attributed to problems with data collection at the beginning of the Great Depression.[22] In the 1930s, working women continued to move into traditionally male professions as well as remaining in traditionally feminine professions, and the laws began to change again. In 1938, the Fair Labor Standards Act outlawed sex as a basis for setting job wage classifications.

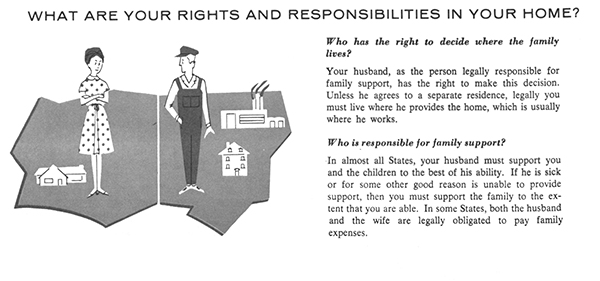

Women famously joined the labor force in droves during World War II, and though the percentage of working women dropped briefly after the war, [23] since 1948 it has risen fairly steadily from around 30% in 1950 to around 60% in 2010. As more women began to work outside the home and societal attitudes continued to change, policies slowly followed. In 1963, the Equal Pay Act outlawed sex-based wage discrimination for the same work, even if the same work had a different job title. In 1964, the Civil Rights Act prohibited discrimination in hiring, wages, employment contracts, and terms of employment on the basis of “race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.” In 1965, a “working wife” was cautioned by the Women’s Bureau that because her husband was legally responsible for family support, he had the right to decide where she lived—but her rights to work, to a bank account, to control her separate property and wages, and to run her own business were well established.

In the past 50 years, women have secured further economic rights. In 1972, Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 outlawed education discrimination on the basis of sex.[24] In 1974, the Equal Credit Opportunity Act made it illegal for banks and financial firms to deny credit on the basis of sex or marital status. In 1978, the Civil Rights Act was amended to outlaw job discrimination because of pregnancy, childbirth, or related medical conditions. In 2009, the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009 made an employer liable for every discriminatory paycheck.[25]

Wage gaps for all women persist, and discrimination remains a challenge,[26] but this Women’s History Month, we can reflect on how far we’ve come.

Browse FRASER materials on women’s economic history in our “Women in the Economy” theme or in the “Women” subject heading.

[1] B. Zorina Khan. The Democratization of Invention: Patents and Copyrights in American Economic Development, 1790-1920. Cambridge University Press, 2005: 128

[2] Claudia Goldin. Understanding the Gender Gap: An Economic History of American Women. Oxford University Press, 1990: 186.

[3] Claudia Goldin. “The Economic Status of Women in the Early Republic: Quantitative Evidence.” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History. Winter 1986: 388-389.

[4] Alexander Hamilton. “Report on the Subject of Manufactures.” Official Reports on Publick Credit, a National Bank, Manufactures, and a Mint. William McKean, 182: 177.

[5] Goldin, 1990: 50.

[6] C. Mildred Thompson. “Women’s Status – Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow,” in “Report on 1948 Women’s Bureau Conference: The American Woman, Her Changing Role: Worker, Homemaker, Citizen.” Women’s Bureau Bulletin, No. 224, 1948: 43.

[7] Law Library of Congress. “Married Women’s Property Laws.” Khan (page 164) notes that the 1839 Mississippi law specifically “protected slave holdings of white married women from seizure by creditors” if her husband owed money.

[8] Goldin, 1990: 189.

[9] Thavolia Glymph. “A Revolution Comes Home.” Slate. November 28, 2017.

[10] Amy Farber. “Historical Echoes: Our Checking Accounts, Ourselves – Or Say Good Night, Gracie’s Checking Account.” Liberty Street Economics, May 18, 2012.

[11] H. Elaine Lindgren. “Women Homesteaders,” in David J. Wishart, ed, Encyclopedia of the Great Plains.

[12] Laine Weber. “Setting the Stage” in “Adeline Hornbek and the Homestead Act: A Colorado Success Story.”

[13] George Robb. “Ladies of the Ticker.” Financial History Magazine, Summer 2017.

[14] Tanya Klich. “A Timeline Of Women And Wealth: The First Female Millionaires, Billionaires & CEOs And The Policies That Paved The Way For Them.” Forbes, March 8, 2017.

[15] Goldin, 1990: 192.

[16] Louis Brandeis. “Brief for Defendant in Error.” Muller v. Oregon. Supreme Court of the United States, October Term, No. 107, 1907.

[17] Harvard University Library Open Collections Program. “Uprising of the 20,000.” Women Working, 1800-1930.

[18] Harvard University Library Open Collections Program. “Muller v. State of Oregon.” Women Working, 1800-1930.

[19] Thomas C. Leonard. Illiberal Reformers: Race, Eugenics & American Economics in the Progressive Era. Princeton University Press, 2016: 169.

[20] Law Library of Congress.

[21] Goldin, 1990: 194-196.

[22] See the commentary on the data in this article: Women’s Bureau. “The Occupational Progress of Women, 1910 to 1930.” Bulletin, No. 104, 1933: 2.

[23] Susan M. Hartmann. The Home Front and Beyond: American Women in the 1940s. Twayne Publishers, 1982. Cited in Metropolitan State University of Denver. “Women Workers in World War II.”

[24] U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights. “Title IX and Sex Discrimination.”

[25] U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. “Equal Pay Act of 1963 and Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009.”

[26] Kim Parker and Cary Funk. “Gender Discrimination Comes in Many Forms for Today’s Working Women.” FactTank. December 14, 2017.

@FedFRASER

@FedFRASER