For many history students, primary resources make history “come alive” and provide more relevant information than just dry facts and dates. Primary sources are documents, artifacts, and objects created by an individual or group as part of daily life.[1] These sources can include photographs, letters, diaries, embroidered samplers, and newspapers.

Letters can deliver a particular view of a historical event or era that may not be found in other primary sources, in addition to offering insight on the cultural landscape of the time. As with any other primary source, letters can be used as single documents to shed light on a specific issue or historical belief. They can also be considered as a group (as in letters exchanged between two or more parties) and used to document an individual’s or group’s actions and communications about a specific issue or historical belief.[2]

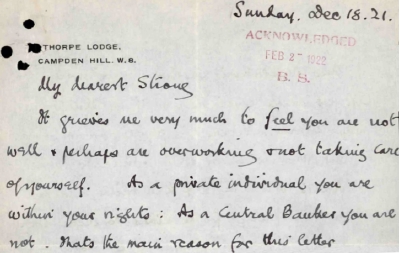

From Strong, Benjamin and Montagu Norman. Correspondence with Great Britain: Letters from Montagu Norman, Governor, Bank of England, 1921. Papers of Benjamin Strong; https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/scribd/?item_id=473608&filepath=/docs/historical/frbny/strong/strong_1116_2_2_norman_1921.pdf&start_page=162#scribd-open.

FRASER’s archival collections are home to several different types of correspondence—personal and professional letters, memos, telegraphs, and even emails—from individuals closely associated with the Federal Reserve System or with banking and financial history. The vast collection of letters from Benjamin Strong (first governor of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York) to Montagu Norman (Governor of the Bank of England) is one example of letters as primary resources. Strong and Norman corresponded quite frequently on a variety of subjects from 1916 to 1928. An exchange of letters between them on September 22 and October 18, 1916, details the intricacies of gold deposits, the use of Federal Reserve notes, and the U.S. currency system alongside an offer of the Elixir of Life, a discussion of vacations, a mention of the “boys in Flanders,” and a report on Strong’s poor health. Each letter begins with a note indicating the last letters received, which helps each correspondent track the conversation and know if any letters may have been lost or not yet received. The men address both personal topics and professional issues in their correspondence. This blending of the personal and professional may seem unusual to modern readers but is common throughout Strong’s letters and other correspondence of that era.

Regardless of the period or topic, letters can be a valuable primary source in many areas of historical research, and FRASER archives offer a wealth of letters and correspondence right at your fingertips.

[1] For a good review of primary sources, check out the Smithsonian’s web page; http://siarchives.si.edu/history/exhibits/stories/what-primary-source.

[2] Eamon, Michael. “A ‘Genuine Relationship with the Actual’: New Perspectives on Primary Sources, History and the Internet in the Classroom.” The History Teacher 39, no. 3 (May 1, 2006): 303-304.